For several months now, 20 teams of Australian high-school students have been designing fuel-cell cars to compete in the country’s inaugural Hydrogen Grand Prix. They’ve been studying up on renewable energy, hydrogen power, and electric vehicles, preparing for the big day in April when their remote-controlled vehicles will rumble for 4 hours in Gladstone, a port city in Queensland. The task: make the most of a 30-watt fuel cell and 14 grams of hydrogen gas.

A few months later and some 800 kilometers up Queensland’s coast, Grand Prix corporate cosponsor Ark Energy aims to apply the same basic hydrogen and fuel-cell components—albeit scaled up more than 3,500 times. By 2023’s third quarter, Ark expects five of the world’s largest fuel-cell trucks to be hauling concentrated zinc ore and finished ingots between a zinc refinery and the nearby port of Townsville. The carbon-free rigs will pack 50 kilos of hydrogen zapped from water using electricity from the refinery’s dedicated solar power plant.

Welcome to Australia, where a green-hydrogen boom is in full swing. Both the massive and the toy-size vehicles are about selling Australians on the transformative potential of green hydrogen—hydrogen gas produced from renewable energy—to decarbonize their fossil-fuel-based economy. And while coal plants still supplied over half of Australia’s power in 2021, change is afoot. The government elected last year passed the country’s first climate-action law in more than a decade. And green hydrogen is the centerpiece of its clean-economy growth plan.

Resource-poor Asian neighbors such as Japan and Korea are also counting on Aussie green hydrogen to help get them off fossil fuels in the decades ahead.

Add up the capacity figures in all of Australia’s current proposals to produce green hydrogen and the sum exceeds Australia’s power-generating capacity. It’s all part of a green-hydrogen wave that’s spreading worldwide.

Observers caution that some of these green-hydrogen projects will never produce a thimbleful of hydrogen—an echo of the hydrogen boom a generation ago that ultimately went bust. “It’s very easy in this current phase for two people you’ve never heard about to create a 30-gigawatt project and put out a press release,” says David Norman, CEO for the clean-energy research organization Future Fuels Cooperative Research Centre in Wollongong, New South Wales.

Phantom projects are not a problem confined to Australia. Only 10 percent of the US $240 billion worth of hydrogen projects announced worldwide are actually moving forward, according to a September 2022 study by consultancy McKinsey & Company. Yet many more are actually needed. Building every electrolyzer promised for 2030 would provide only about one-sixth of the green hydrogen required to meet climate targets, according to figures from the International Energy Agency in Paris.

Amid this noisy background, Queensland is home to the two projects most likely to boost the credibility of Australia’s green-hydrogen juggernaut in 2023. Ark Energy’s project is part of a clean-energy blitz in Australia by its parent company, Seoul-based metal-refining giant Korea Zinc. The other glimmer of reality is a project in Gladstone to build one of the world’s largest electrolyzer-manufacturing plants, which promises to provide a local source of equipment amid ongoing chaos in global supply chains.

Why a hydrogen truck?

The 124-megawatt solar plant adjacent to Korea Zinc’s Townsville refinery, completed in 2018, cut a quarter of the coal-heavy grid power it had been using to run its power-intensive electrolytic process. The coming fuel-cell trucks will trim its diesel consumption.

Ark Energy CEO Daniel Kim says Korea Zinc launched his firm in 2021 to help shift its Australian operations to 80 percent renewable energy by 2030 and, in the process, pave a path for 100 percent renewable energy group-wide by 2050. Kim says the 2050 goal requires green hydrogen—or a more exportable fuel made from it—because Korea Zinc does most of its refining in South Korea, where there’s limited space for solar and wind plants.

Ark’s first move was to access more renewable power in Australia by buying into a 923-MW wind farm that’s expected to spin up in 2024. Next it ordered equipment for the Townsville truck project to begin exploring green hydrogen’s capabilities and challenges. “To become a low-cost producer of green hydrogen, we first have to become an extreme user—to make it pervasive across our business. Diesel replacement for heavy trucks was the best prospective use,” Kim says.

Today, 28 heavy-duty diesel-powered trucks operate at the Townsville refinery. When ships arrive at port with zinc concentrate, or tie up to take on zinc ingots, the rigs haul triple-trailers and loop the 30 km from port to plant and back nonstop for as many as eight days. Time is money, says Kim, because occupying a berth in port can cost a whopping AUS $22,000 (US $13,800) a day. Even if a battery-powered truck could handle the refinery’s 140,000-tonne loads, Kim says his company couldn’t afford to wait for batteries to recharge.

Fortescue’s growth plan anticipates shipping most of its green hydrogen out of Australia to clean up heavy vehicles, industries, and power grids worldwide.

In 2021, Ark Energy took a stake in Hyzon Motors, one of the few firms working on ultraheavy trucks powered by fuel cells. Hyzon, based in Rochester, N.Y., agreed to equip some of its first extra-beefy fuel-cell rigs with the right-hand drive and wider carriage required in Australia—something other developers couldn’t offer until 2025 or 2026. “We’re bringing forward the transition of Australia’s ultraheavy transport sector by several years,” says Kim.

To fuel the trucks, Ark Energy ordered a 1-MW electrolyzer from Plug Power, based in Latham, N.Y. Kim anticipated that construction of the electrolyzer facility would start around the end of 2022, and vowed that five fuel-cell trucks would be looping to port and back on hydrogen gas in the third quarter of 2023 or sooner.

Kim says these vehicles will cost “a little over three times” that of an equivalent diesel-fueled hauler, up front, but the overall project should break even or even save money over the trucks’ projected 10-year operating life. Government grants and loans and high diesel prices help make hydrogen competitive. The trucks’ unchanging route was also a plus: The relatively flat loop enabled use of a smaller, cheaper, fuel cell. “This is a dedicated truck for a dedicated purpose,” Kim notes.

Exporting green hydrogen

Ark Energy expects to start exporting renewable energy around 2030. In contrast, the team delivering Queensland’s second dose of green hydrogen realism this year could begin commercial-scale exports in 2025. The AUS $114 million (US $72 million) electrolyzer plant rising in Gladstone is the first brick-and-mortar green-hydrogen move by mining magnate Andrew Forrest, Australia’s boldest, and wealthiest, green-hydrogen proponent.

Forrest became the second-richest man in Australia running Perth-based Fortescue Metals Group, which disrupted the global iron-ore business through vertical integration and aggressive cost cutting.

Now Fortescue is applying the same strategy to green hydrogen. Forrest vows to invest US $6.2 billion to produce 15 million tonnes of green hydrogen per year by 2030—50 percent more than what the European Union says it needs to import to get off Russian energy and to cut carbon emissions. Doing so will require about 150 GW of wind and solar generation—more than the total installed generating capacity of France. The move is projected to eliminate 3 million tonnes of carbon per year—slashing Fortescue’s emissions to zero and saving it US $818 million per year.

BloombergNEF predicts that the annual manufacturing capacity worldwide for hydrogen-producing electrolyzers will more than triple in the next two years.

Cameron Smith, head of manufacturing for Fortescue’s green-energy subsidiary, Fortescue Future Industries, says getting there means cutting costs until the company’s renewable energy is cheaper than fossil fuels. “Our objective here is to make fossil fuels irrelevant,” Smith declares.

Fortescue is building its own electrolyzer production plant in spite of a global glut. Market analysts at BloombergNEF project that manufacturing capacity for electrolyzers will exceed demand 10- to 15-fold this year. Smith says that’s not a major concern for Fortescue, given the company’s imperative to cut costs and to quickly bring green-hydrogen production on line. “We don’t need to make everything, but we need a credible pathway to do so if we can’t get the equipment we need at the cost and quality we need to make all our projects viable,” he says.

The Gladstone plant’s 13,000-square-meter envelope is already in place, and Smith anticipates installation of one line’s robotic machines during the second quarter of 2023. He expects the plant will end the year as a “gigawatt-scale” electrolyzer factory: producing enough electrolyzers in a year to consume 1 GW of electricity. And he expects production capacity to double with a second line early in 2024.

The problem with shipping hydrogen

Fortescue expects green hydrogen to help its own operations reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2040. But its growth plan, like Ark Energy’s, anticipates exporting most of its green hydrogen to clean up heavy vehicles, industries, and power grids worldwide. First, though, they will have to make it shippable.

Shipping hydrogen is pricey. As either a gas or a liquid, it has relatively low volumetric energy density. So most of Australia’s prospective green-hydrogen mega-producers expect to move their energy overseas by converting green hydrogen to ammonia—a chemical precursor for nitrogen fertilizers that already ships worldwide. Ammonia is primarily produced from hydrogen, although today it’s typically done using hydrogen made with natural gas rather than electrolysis.

Exported ammonia made in Australia from green hydrogen could already outcompete ammonia produced in Europe with natural gas, according to calculations by BloombergNEF, and proposed projects are multiplying. Ark Energy recently formed an industrial consortium to use 3 GW of renewable power to produce “green ammonia” for export to Korea, although first shipments wouldn’t happen until after 2030.

Fortescue has even bigger long-term plans, and is already sizing up a way to jump-start ammonia exports. It is considering refitting a 54-year-old fertilizer plant in Brisbane, which was slated to shut down early this year due to skyrocketing natural-gas prices. Fortescue and the plant’s owner are considering installing 500 MW of electrolyzers so they can restart the plant on green hydrogen around 2025.

“It’s very easy in this current phase for two people you’ve never heard about to create a 30-gigawatt project and put out a press release,” says one observer.

Amid all of these grand plans, what remains to be seen, says hydrogen analyst Martin Tengler at BloombergNEF’s Tokyo office, is whether green-ammonia exports can truly meet people’s energy needs.

Ammonia doesn’t burn well on its own, he notes, and converting exported ammonia back to hydrogen for steel plants or fuel-cell vehicles requires a lot of energy. “You’re using energy to import energy. If you need green hydrogen in Europe, it’s probably cheaper to make green hydrogen in Europe,” Tengler concludes.

Some plans for green ammonia could actually extend fossil-fuel consumption and thus delay climate action. For example, some Japanese and Korean power producers have announced plans to burn green ammonia in coal-fired power plants to reduce emissions.

In September, BloombergNEF estimated that power from Japanese coal plants burning 50 percent green ammonia from Australia would cost US $136 per megawatt-hour in 2030—more than it projects for power from offshore wind and solar plants in Japan backed up with battery storage. “It’s not the most economical way to use ammonia,” Tengler says, “or the cheapest way for Japan and Korea to decarbonize.”

In other words, even if green hydrogen gets real this year, there’s much to learn about what it should be used for, and where.

Reference: https://ift.tt/VRAweP8

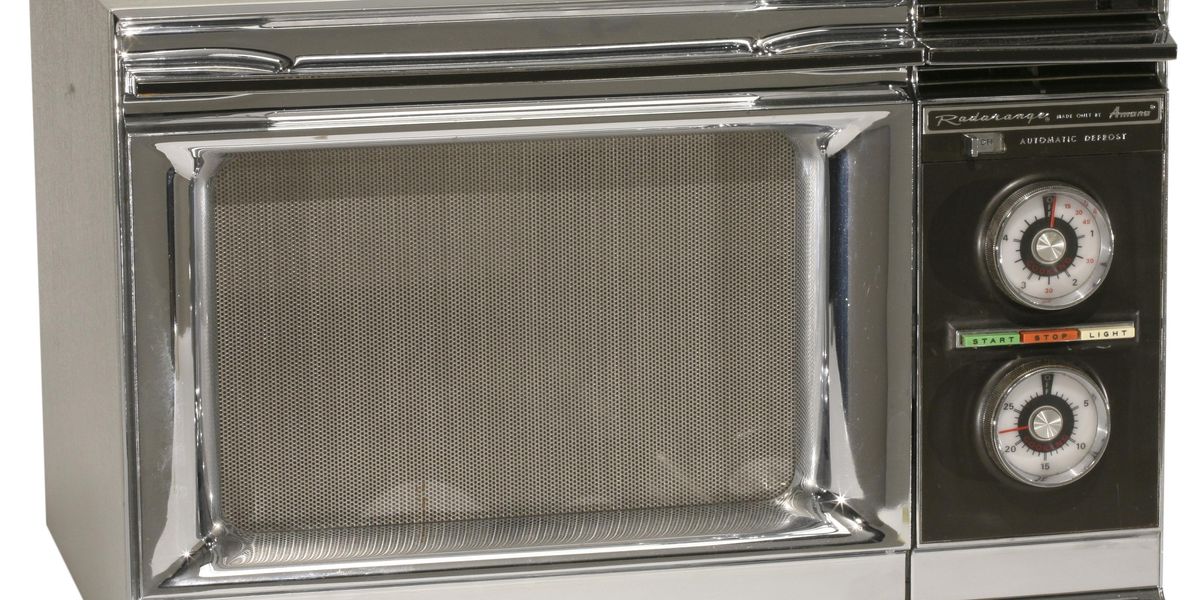

The Tappan RL-1, introduced in 1955, was the first microwave oven intended for home use. Note the handy recipe drawer at the bottom.

The Tappan RL-1, introduced in 1955, was the first microwave oven intended for home use. Note the handy recipe drawer at the bottom. The author’s Amana Touchmatic Radarange microwave oven dated from 1980. Its previous owner kept meticulous notes on how to use it. Allison Marsh

The author’s Amana Touchmatic Radarange microwave oven dated from 1980. Its previous owner kept meticulous notes on how to use it. Allison Marsh

An AST SpaceMobile employee sets up a test unit of the BlueWalker 3 satellite’s modular antenna array; the final array includes 148 such units.AST SpaceMobile

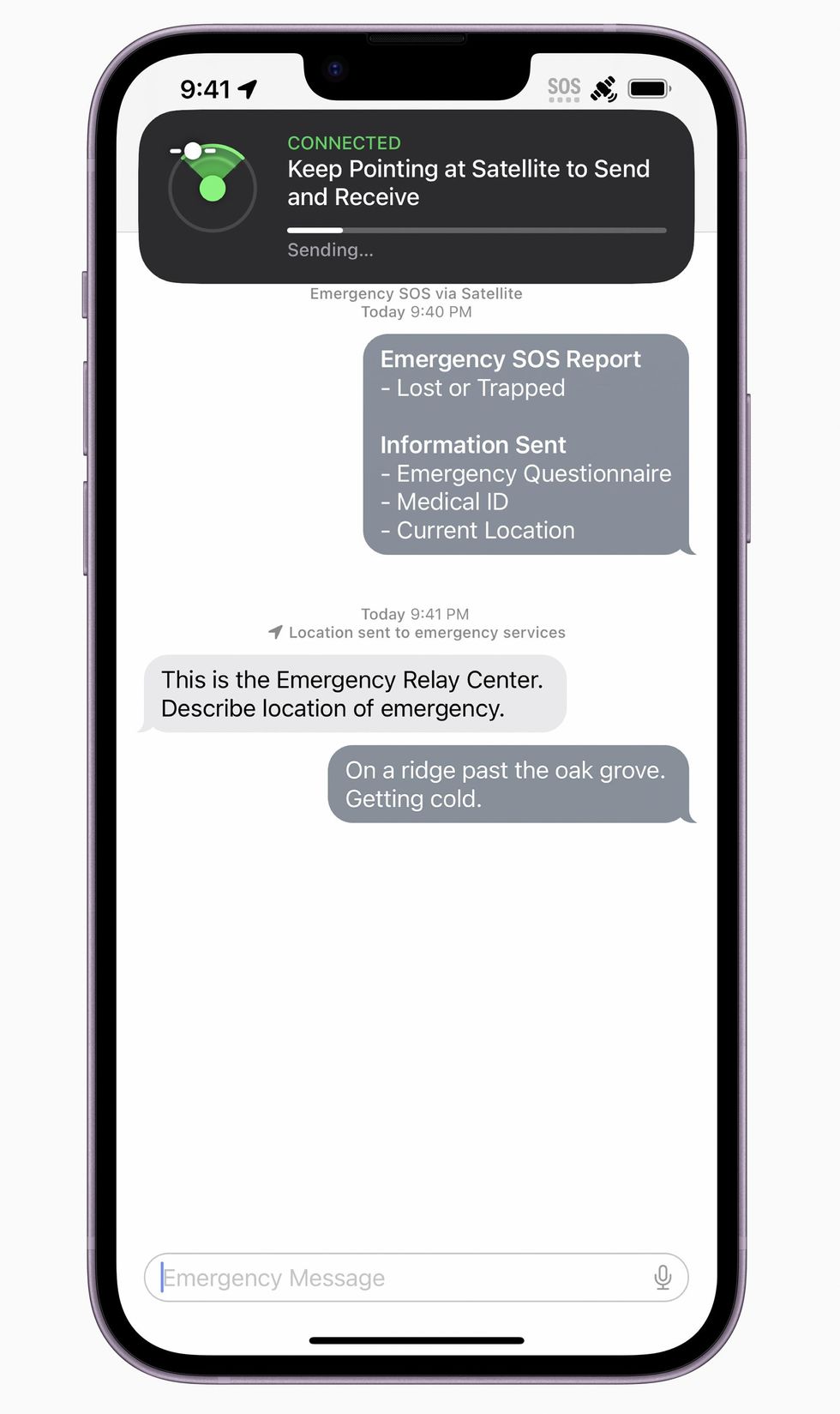

An AST SpaceMobile employee sets up a test unit of the BlueWalker 3 satellite’s modular antenna array; the final array includes 148 such units.AST SpaceMobile his mock-up shows the app for Apple’s Emergency SOS via satellite, which enables emergency texting in areas with no terrestrial coverage.Apple

his mock-up shows the app for Apple’s Emergency SOS via satellite, which enables emergency texting in areas with no terrestrial coverage.Apple

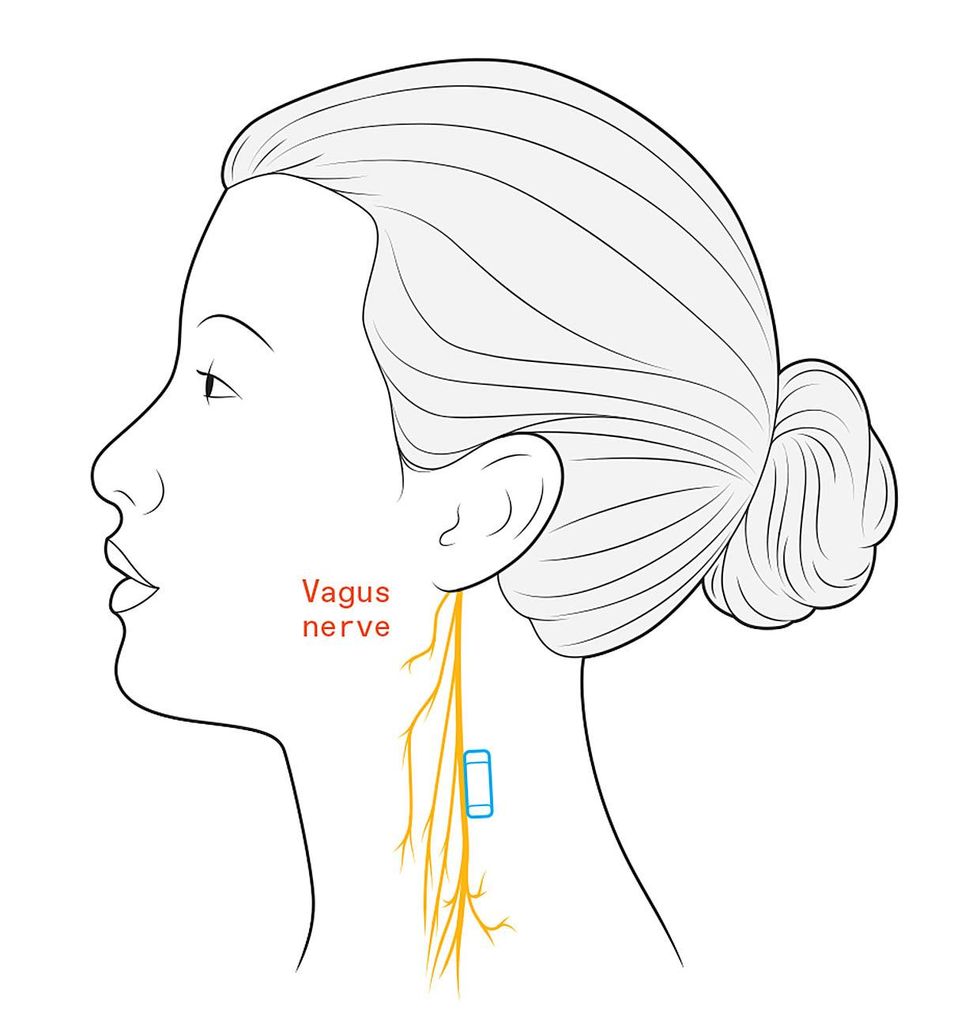

The SetPoint implant is inserted beside the patient’s vagus nerve, which travels down from the brain to innervate the spleen and other vital organs.Chris Philpot

The SetPoint implant is inserted beside the patient’s vagus nerve, which travels down from the brain to innervate the spleen and other vital organs.Chris Philpot SetPoint shrank the vagus nerve stimulator so that it can be implanted in a patient’s neck instead of the chest.SetPoint Medical

SetPoint shrank the vagus nerve stimulator so that it can be implanted in a patient’s neck instead of the chest.SetPoint Medical

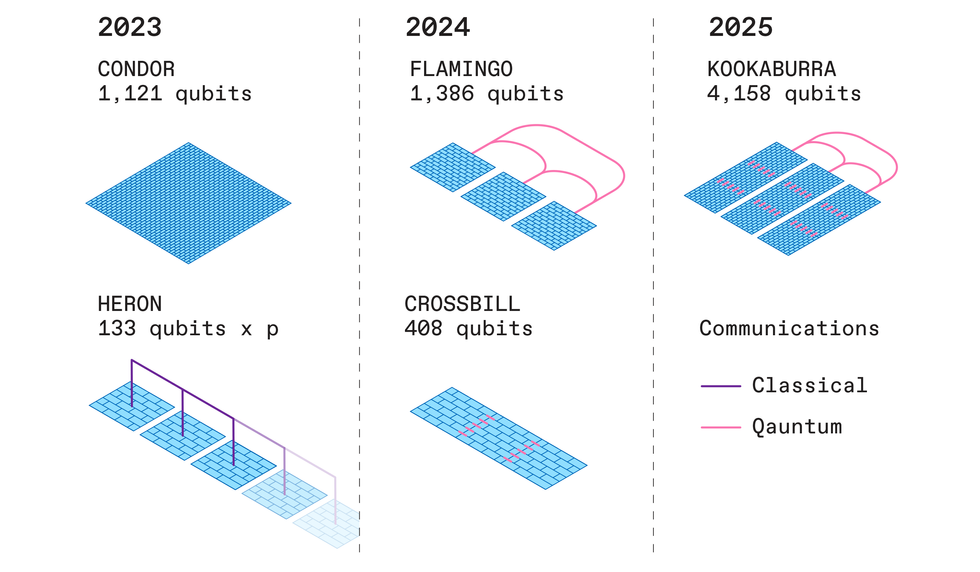

IBM expects to build quantum computers of increasing complexity over the next few years, starting with those that use the Condor processor or multiple Heron processors in parallel.Carl De Torres/IBM

IBM expects to build quantum computers of increasing complexity over the next few years, starting with those that use the Condor processor or multiple Heron processors in parallel.Carl De Torres/IBM