As I write this month’s article, my house is a noisy, dusty construction zone. I am renovating my kitchen, which was originally built in 1964. Although I’m happy to be rid of some of the disastrous 1960s design missteps—seriously, only one electrical receptacle in the entire kitchen?—I was sad to part with a small piece of history: my Amana Touchmatic Radarange microwave oven, with its 700 watts of glorious electromagnetic cooking power.

The ever evolving and revolving microwave oven

My Radarange was installed by the previous homeowner in 1980 and had a decidedly vintage feel, but it was actually a third-generation model. The original Radarange came out in 1947 and was intended for commercial kitchens. Two years prior, Raytheon engineer Percy Spencer had filed a patent for a “Means for Treating Foodstuff,” and the company tested the oven in a Boston restaurant. This water-cooled model was the size of a modest refrigerator, standing approximately 1.7 meters tall and weighing 340 kilograms. It would take a while for the microwave oven to evolve into the countertop version we all know today.

Raytheon first entered the consumer market in 1955, but not with the Radarange. Instead, it licensed the technology to Tappan, a maker of conventional stoves that had pioneered the “see-through” glass oven door. Tappan produced the RL-1 microwave oven for home use with an initial retail price of $1,295 (about $14,400 today). With that price tag, it was obviously meant to impress.

The Tappan RL-1, introduced in 1955, was the first microwave oven intended for home use. Note the handy recipe drawer at the bottom.Division of Work and Industry/National Museum of American History/Smithsonian Institution

The Tappan RL-1, introduced in 1955, was the first microwave oven intended for home use. Note the handy recipe drawer at the bottom.Division of Work and Industry/National Museum of American History/Smithsonian Institution

I love the personal, homemaker feel of the built-in recipe card drawer in the bottom of this wall-mounted unit. Tappan produced only 34 microwaves in its first year, but it continued to have steady growth. It sold 1,396 units by the time production ceased in 1964.

Meanwhile, other companies were also testing the market. In April 1961, Sharp demonstrated a 2-kilowatt microwave prototype at the International Trade Fair in Tokyo. The following year the company released the R-10, a 1-KW model intended for restaurants and commercial use and priced at 540,000 yen (about $18,600 today). In 1966, Sharp introduced the R-600, the first microwave oven with a revolving turntable to help cook food more uniformly. The R-600 was compatible with standard household power sources and intended for home use, but at 200,000 yen ($5,600 today), it was still a luxury good. In the fall of 1967, Sharp debuted the R-1000, a commercial microwave with a new feature that’s still more or less with us: a bicycle bell that dinged when the cooking time ended.

To reenter the consumer market for microwave ovens, Raytheon in 1965 acquired Amana Corp., a manufacturer of home appliances based in Iowa. Two years later, Amana introduced the second generation of the Radarange, this one a compact model designed for the modern home kitchen. The price had fallen drastically, to $495 ($4,400 today)—still very expensive for the average household, but microwave ovens were gaining ground. In 1975 sales of microwave ovens in the United States outpaced those of conventional gas ovens for the first time. Consumers were sold on the convenience and futuristic power of quick cooking.

A case study in microwave cooking

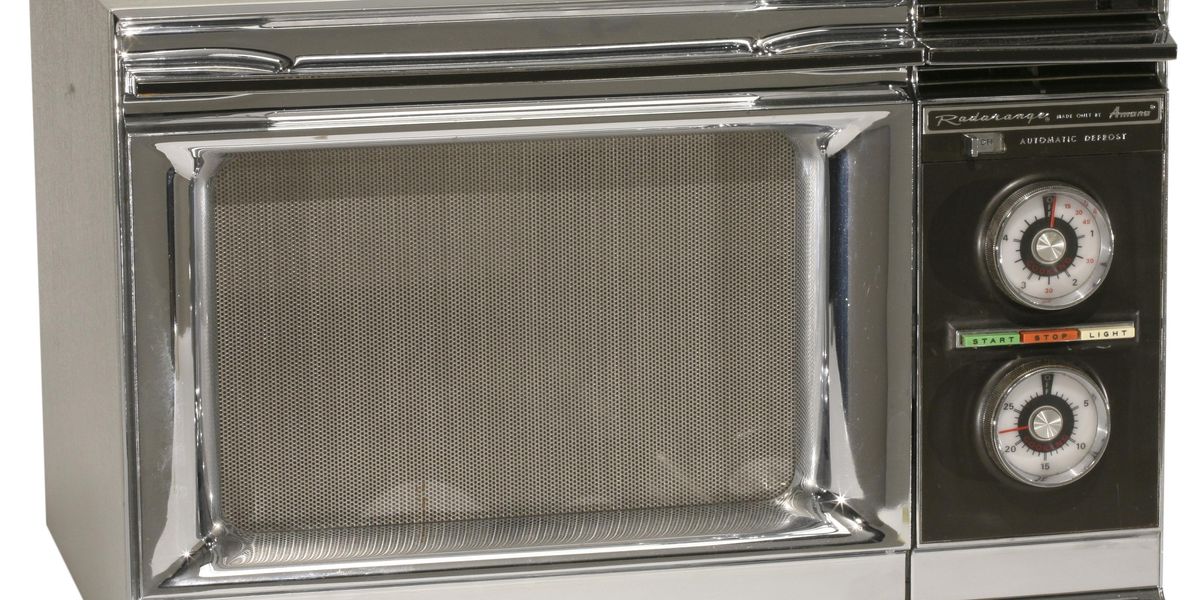

The author’s Amana Touchmatic Radarange microwave oven dated from 1980. Its previous owner kept meticulous notes on how to use it. Allison Marsh

The author’s Amana Touchmatic Radarange microwave oven dated from 1980. Its previous owner kept meticulous notes on how to use it. Allison Marsh

The technology at the heart of the microwave oven is the cavity magnetron, developed during World War II for radar detection. A 1958 article in Reader’s Digest popularized the story of Percy Spencer’s accidental discovery that the cavity magnetron could heat food. But abundant documentation in the form of lab notebooks, patent filings, government reports, and office memos indicates that a series of observations led to the concept of the microwave oven, not a single eureka moment.

As the microwave oven transitioned from the laboratory to modern life, one aspect was not well documented: How did consumers learn to use this new appliance? The lack of such a paper trail is not so surprising. Did you save any notes on how to use your first smartphone? For these types of stories, historians often look for microhistories or individual case studies to draw broader conclusions about society. Lucky for me, Marion Steen, the gentleman who sold me his house, was extraordinarily organized and detail oriented. When I bought the house, he handed over a bundle of documentation for all of the appliances, including a three-ring binder containing handwritten notes on how to use the microwave.

Here’s what I learned: On 15 July 1980, Steen attended a class hosted by Susan Ambrose at the Display Center in West Columbia, S.C., to learn how to use his newly purchased Amana Radarange. He noted that microwaves cook by reflection, absorption, and transmission. Steen didn’t elaborate but according to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, that’s exactly right. The magnetron produces microwaves, which are reflected within the metal interior of the oven. The food absorbs the microwaves, causing the water molecules to vibrate and produce heat, which in turn cooks the food. But microwaves penetrate only 1 to 2 centimeters into food, so only the outer layers of thicker pieces get directly cooked by microwaves; the interiors are cooked through the conduction of heat from the outside. The water content may vary across a dish, so a sauce may be boiling hot while a piece of meat may still be cold. Steen’s notes emphasize “Give some ‘standing time’ after cooking!!” This allows the heat to disperse more uniformly throughout the food.

Steen must have gone all in on the specialty cookware for his new microwave. Included in his binder are pamphlets for the Amana Radarange Popcorn Popper, the Amana Browning Skillet, the three-piece Amana Radarware Cook Kit (which included a browning grill, a 3-quart casserole made of Pyrex, and a roasting rack that doubled as a serving dish), and the Corning Ware Micromate browners. Steen didn’t leave behind any of these items, but the descriptions of the browners intrigued me. Made by Corning Glass Works for Amana, they had browning surfaces coated with tin oxide. The dishes had to be preheated empty in the Radarange. The coating would absorb the microwaves, causing the surface to become hot and turn yellow. Food pressed onto these surfaces would brown in 1 to 2 minutes, and then you’d flip it to brown the other side. Sure, you could achieve the same results in a skillet on your stove, but you have to admire the ingenuity at work here.

Included in all the cookware booklets are recipes. I love experimenting with recipes from old cookbooks, but some of these seem like a stretch. Would you really use your Amana Radarange Popcorn Popper to make popcorn, which you then grind up and add to meatloaf, which you then cook in your Amana Radarange?

Microwave manufacturers weren’t the only ones trying to educate consumers on how to use the new appliance. Packaged food manufacturers and plastic-wrap makers saw a new market for their products and created special recipe booklets. In my fabulous three-ring binder, I have “Microwave Cooking with Kellogg’s,” “Basic Instructions for Making Pillsbury Plus Cake Mixes in the Microwave Oven,” and “Saran Wrap & Microwave…The Perfect Pair!” Swanson, a longtime maker of frozen dinners, changed its packaging from aluminum trays to a “heat ’n serve” tray that could be used in either microwave or conventional ovens.

The Introduction to Cooking with the Amana Radarange Cookbook promises home chefs that they can make almost anything in a microwave. In his handwritten notes, Steen included directions on how to cook a roast (“15 minutes on full power, add vegetables, then 45 minutes on level 5”), scramble eggs (“always break yolks”), and bake a cake (“must use the special Bundt pan”—underlined twice for emphasis). What is missing is the outcome of these recipes. Call me a skeptic, but these are three things I have never made successfully in a microwave.

Steen, a native southerner, must have been heartbroken to write down, “Don’t cook biscuits in microwave.” My colleague Carol Harrison has a similar vivid memory of biscuit failure. Learning to cook with a microwave as a teenager, she tried to make simple refrigerator biscuits, but they didn’t brown. She kept adding time, but they still didn’t seem done. When she finally took them out, the outside remained a pale white, but the inside had turned to inedible charcoal.

As the Amana cookbook noted, breads don’t brown in a microwave oven. The book suggested using toppings such as rye or whole wheat flour to supply color, which seems a bit disingenuous. The lack of browning didn’t stop Amana from listing almost 20 pages of bread and muffin recipes.

An avid cook myself, I like to annotate my cookbooks with who in the family liked what recipes, minor alterations in ingredients, and changes to the directions. Sadly, Marion Steen left no such notes behind. I do not know what he cooked in his Radarange or how it tasted, and so I am left with only half the story.

In my new kitchen, I have opted for a microwave drawer. This technology, developed by Sharp and brought to market in 2005, fits under the counter of the kitchen island. Although it has a lovely, sleek design, I chose it for practical reasons. The impetus for renovating came when my mother moved in with me last year. We are designing things to be as accessible as possible so that she can age in place. With a microwave drawer, she no longer has to lift plates above her head to reheat food, as she did with the over-the-stove Radarange. I only hope that Sharp can deliver 40-plus years of reliability like my Radarange did.

Part of a continuing series looking at historical artifacts that embrace the boundless potential of technology.

An abridged version of this article appears in the January 2023 print issue as “The Microwave’s Slow Burn.”

Reference: https://ift.tt/kPoYLUM

No comments:

Post a Comment