Monique Robroek once had such crippling arthritis that, even with the best available medications, she struggled to walk across a room. But thanks to an electronic implant fitted under her skin, she managed to wean herself off all her drugs and live pain-free for nearly a decade—until recently, when a viral illness made her rheumatoid arthritis (RA) flare up again.

Robroek’s long remission is “very impressive” and rare among patients with RA, says her doctor Frieda Koopman, a rheumatologist at Amsterdam UMC, in the Netherlands. Robroek’s experience highlights the immense potential of so-called bioelectronic medicine, also known as electroceuticals, an emerging field of treatment for diseases that have traditionally been managed with pharmaceuticals alone.

Robroek is also an outlier, though. Koopman led a landmark 17-person trial that tested whether modulating the nervous system’s electrical-signaling patterns could tamp down inflammation and joint pain in RA. Robroek was one of only a handful who achieved appreciable and sustained reductions in disease severity, according to the 2016 paper.

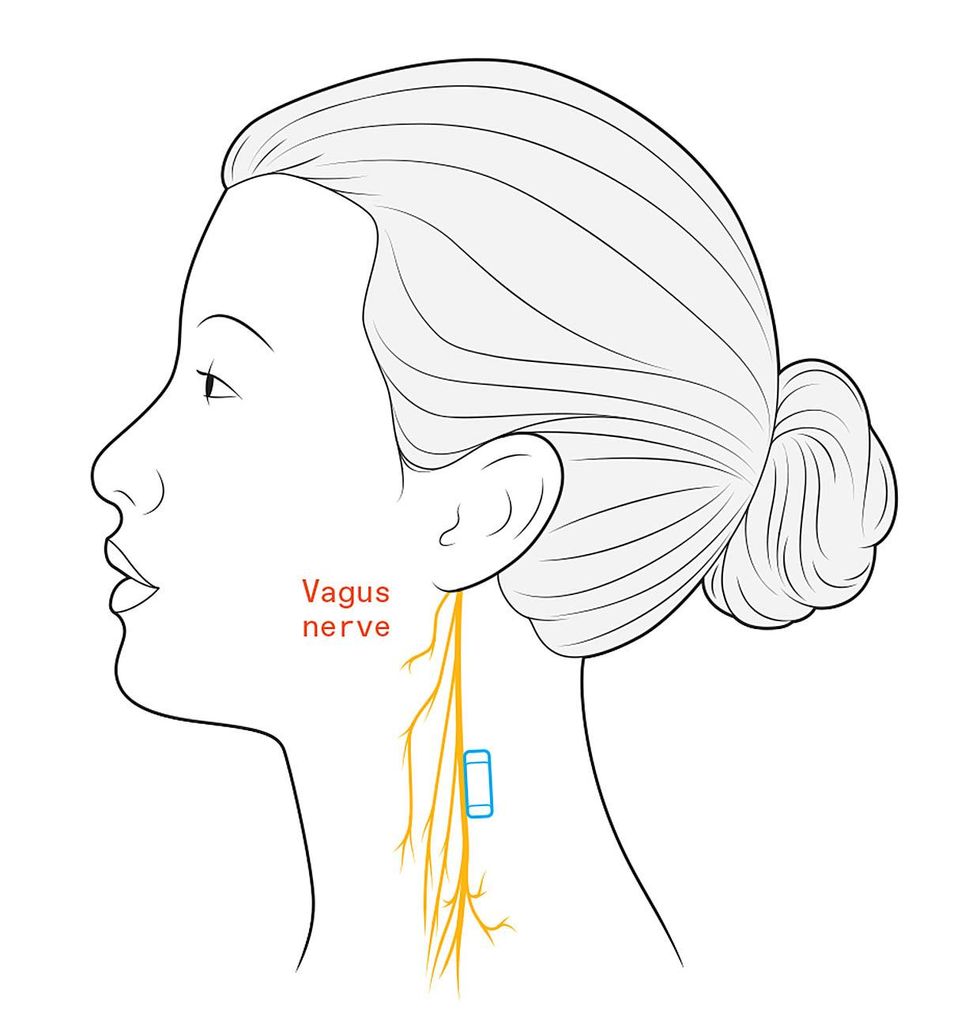

The SetPoint implant is inserted beside the patient’s vagus nerve, which travels down from the brain to innervate the spleen and other vital organs.Chris Philpot

The SetPoint implant is inserted beside the patient’s vagus nerve, which travels down from the brain to innervate the spleen and other vital organs.Chris Philpot

Pilot studies like Koopman’s are one thing, but scientific certainty demands randomized, sham-controlled trials. Doctors, neuroscientists, and bioengineers should soon get a better sense of the performance of electroceutical devices. In late 2023, SetPoint Medical, the Valencia, Calif., company that sponsored Koopman’s initial trial, will report preliminary findings from Reset-RA, the first large-scale examination of nerve stimulation for an autoimmune condition. Like the earlier trial, the Reset-RA study targets the vagus nerve, the main conduit of brain–body communication, in an attempt to fight inflammation.

Expectations are charged. Although devices that harness electrical impulses are already widespread in medicine, these platforms all tap into neural circuits that directly impact diseased tissues; for example, deep-brain stimulators help with symptoms of Parkinson’s disease by hacking the brain’s motor control center. None take aim at what Kevin Tracey, in an influential 2002 article, termed the “inflammatory reflex,” a neural network that indirectly regulates immune responses to infection and injury through the vagus nerve and its connected organs.

Tracey, a former neurosurgeon who leads the Feinstein Institute for Medical Research in Manhasset, N.Y., was the first to show that vagus nerve stimulation in rats could suppress the release of immune-signaling molecules. He later linked the effect to vagus nerve signals running into the spleen, a fist-size organ in the abdomen where immune cells are activated. In 2007, Tracey cofounded SetPoint to bring the treatment to the clinic.

The company first repurposed an off-the-shelf implant used to control seizures in people with epilepsy. SetPoint optimized the stimulation parameters, using rodent studies for guidance, before giving the devices to patients like Robroek. She and the other recipients each had a cookie-size pulse generator surgically placed inside their chests. A wire snaked up the left side of the neck, where an electrode wrapped around the vagus nerve. It gave a gentle, 1-minute buzz of stimulation up to four times every day.

The study targets the vagus nerve, the main conduit of brain-body communication, in an attempt to fight inflammation.

Paul Peter Tak, an immunologist and biotech entrepreneur who led the trial with Koopman, was worried that patients with RA might not want to undergo surgery and have hardware implanted under their skin. But after publicizing the study on Dutch television, Tak was inundated with requests from patients who were sick of endless regimens of pills and injections. “This was my unplanned market research,” Tak says. “To my surprise, there are many patients who might prefer a one-and-done surgery.”

While the study’s results were promising, the device itself was cumbersome. So SetPoint overhauled the platform, shrinking it down to a peanut-size neurostimulator with integrated electrodes and a wirelessly rechargeable battery, all encased inside a silicone holding pod that sits directly atop the vagus nerve in the neck. “It’s like going from an old car to a Tesla—it’s completely redesigned,” says SetPoint’s chief medical officer, David Chernoff.

A small trial performed in 2018 demonstrated that this miniaturized device was safe. The 250-person Reset-RA study, in which half the participants receive no stimulation for the first 12 weeks after implantation, is now evaluating efficacy. If it works, trials for other autoimmune diseases could follow.

SetPoint shrank the vagus nerve stimulator so that it can be implanted in a patient’s neck instead of the chest.SetPoint Medical

SetPoint shrank the vagus nerve stimulator so that it can be implanted in a patient’s neck instead of the chest.SetPoint Medical

Other companies, meanwhile, are testing devices that target nerves closer to the site of immune activation—“at the business end,” says Kristoffer Famm, president of the British company Galvani Bioelectronics. This end-organ approach to nerve zapping, argues Famm, should allow for more precise, disease-specific neuromodulation, without the off-target effects of shocking the vagus nerve, which is central to many bodily processes.

A joint venture between Google’s parent company, Alphabet, and the British pharmaceutical company GSK, Galvani is now evaluating its implantable splenic nerve stimulator in small numbers of patients with RA. Another company called SecondWave Systems, headquartered in Minneapolis, is also testing whether spleen-directed ultrasound waves can offer the same immune-quelling effects without the burden of invasive surgery. Both Galvani and SecondWave expect to announce first-in-human data within the next year.

“Neuromodulation is definitely having a moment,” says Gene Civillico, a neurotechnologist at Northeastern University, in Boston, who previously oversaw bioelectronics research efforts at the U.S. National Institutes of Health. “Controlling nervous tissue in a spatially and temporally precise way is going to be the way that we cure or modify a lot of disease states,” Civillico contends. In the coming year, SetPoint and other companies hope to prove him right.

Reference: https://ift.tt/WHFCkJn

No comments:

Post a Comment