Critical considerations pertinent to connected autonomous vehicles, such as ethics, liability, privacy, and cybersecurity, do not share the same spotlight as the CAVs’ benefits. Although CAVs’ abilities to reduce the number of fatal accidents and to consume less fuel receive most of the attention, the vehicles’ challenges are equally worthy of discussion.

In a trio of IEEE Standards Association webinars—now available on demand— experts discuss issues surrounding autonomous mobility, topics not often covered in the mainstream news media.

Ethical concerns

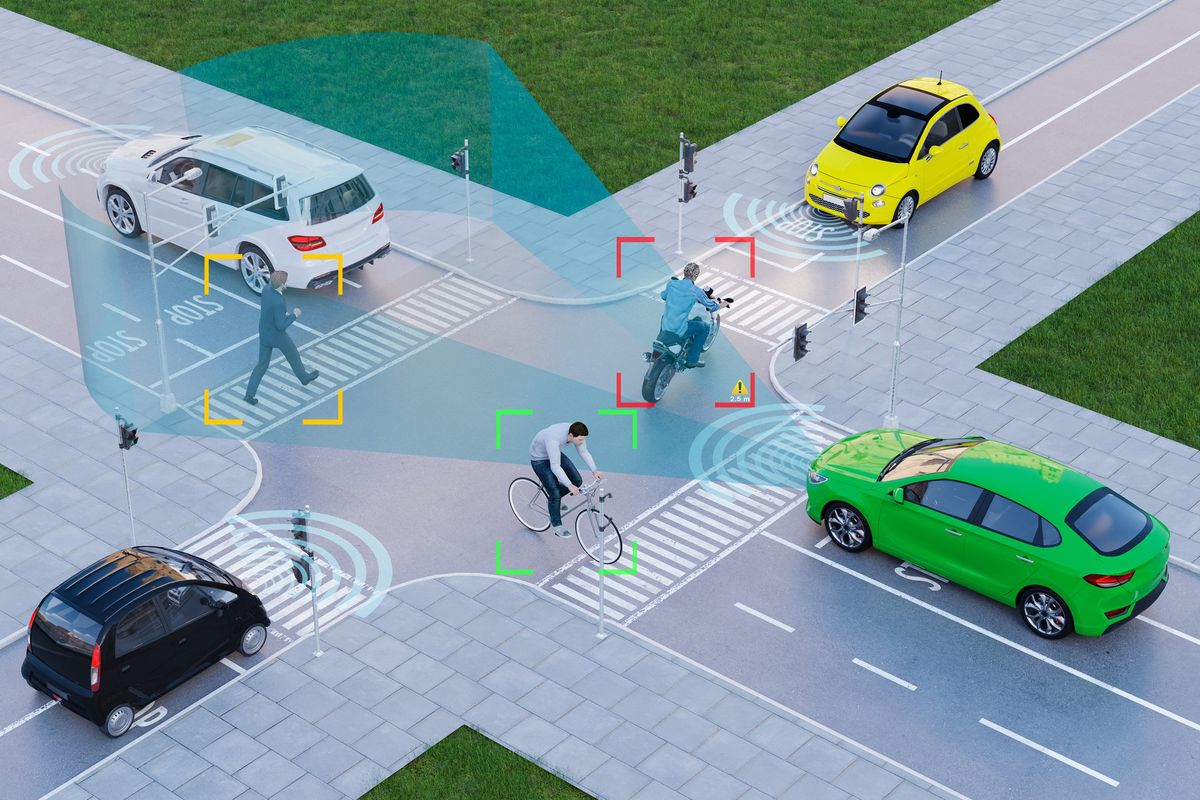

When it comes to ethics, the main focus seems to be on how artificial intelligence helps a CAV recognize people, objects, and traffic situations.

In the Behind the Wheel: Who Is Driving the Driverless Car? webinar, IEEE Fellow Raja Chatila, professor emeritus at the Sorbonne University in France and a member of the country’s National Pilot Committee for Digital Ethics, pointed to one early example. It involved training an AI system to recognize images of similar-looking humans. But it did not include dark space, and as a result, the system could not identify people of color, a situation that could prove disastrous in autonomous driving applications.

Probably the most controversial ethics issue is the belief that CAVs should be able to make life-saving decisions similar to those presented in a popular experiment focusing on ethics and psychology: the so-called trolley problem. In the scenario, the driver of a trolley car faces an imminent collision on the track and has only two options: do nothing and hit five people on the track, or pull a lever to switch the track and set the trolley on a collision course with one person.

In reality, a CAV doesn’t need to make ethical or moral decisions. Instead, it must assess who and what is at greater risk and adjust its operations to eliminate or minimize damages, injuries, and death. Ethically speaking, CAVs, which use machine learning or artificial intelligence, must perform accurate risk assessment based on objective features and not on characteristics such as gender, age, race, and other human identifiers, Chatila said.

Assigning liability

If a CAV is involved in or causes a serious accident, who is at fault? The vehicle, the human driver, or the manufacturer? Clearly, if the vehicle has a manufacturing defect that’s not addressed with a recall, then the manufacturer should assume a greater level of responsibility.

The question then remains: Who or what is liable in the event of an accident? The manufacturer might claim that, as manual control of the vehicle is available, the driver is liable. The driver, however, could claim some malfunction of the manufacturer’s automated system is to blame. Finger-pointing is not the solution.

The Human vs. Digital Driver webinar covers those and similar homologation issues. Homologation involves the process of certifying that vehicles are roadworthy and match criteria established by government agencies responsible for road safety.

The webinar discusses six levels of driver assistance technology advancements that self-driving cars might advance through:

- Level 0: Momentary driver assistance (complete driver control; no automation; a driver is mandatory).

- Level 1: Driver assistance (minor automation such as cruise control; driver intervention required).

- Level 2: Additional assistance (partial automation; advanced driver-assistance systems such as steering and acceleration control; driver intervention required).

- Level 3: Conditional automation (environmental detection; vehicle can perform most driver tasks; driver intervention required).

- Level 4: High automation (extensive automation; driver intervention is optional).

- Level 5: Full automation (full driving capabilities; requires no driver intervention or presence).

The CAV industry is not yet up to Levels 4 and 5.

Privacy considerations and traffic law changes

Privacy and cybersecurity issues have become ubiquitous in every application with CAVs, posing their own concerns, as mentioned in the Risk-Based Methodology for Deriving Scenarios for Testing Artificial Intelligence Systems webinar.

A vehicle need not be autonomous to experience privacy invasions. All that’s necessary is a GPS tracking system and or one or more occupants with a smartphone. Because both technologies rely on software, potential protection against cyberattacks in CAVs is questionable at best.

The vehicles use many software programs, which require regular updates that extend their existing functionality while also adding functions. Most likely, the updates are done wirelessly via 5G.

Anything employing wireless connectivity is fair game for hackers and cybercriminals. In a worst-case scenario, a hacker could take control of a CAV with passengers onboard.

Critical considerations pertinent to connected autonomous vehicles such as ethics, liability, privacy, and cybersecurity do not share the same spotlight as the CAVs’ benefits.

So far, such situations have not been widespread, but more work and due diligence are necessary to stay ahead of hackers.

Meanwhile, CAVs collect large amounts of data. They collect images of pedestrians without the pedestrians’ or vehicle owner’s consent. There currently are no regulations on how much data is collectible, who can access the data, or how it’s distributed and stored. Essentially, the data is usable for a plethora of purposes that could compromise a person’s privacy. Paired with the ability to transmit the images wirelessly, this aspect also leaks into the ethics domain.

Complying with differing traffic laws is another concern. Drivers know that speed limits change, lanes merge or widen, detours are common, and other traffic changes happen. They learn to adjust by observing road signs or taking cues from police officers directing traffic. But can CAVs observe such changes?

Outfitted with cameras, advanced driver-assistance systems, software, and sensor technologies, the basics should be easy for the vehicles to tackle. Cameras and image sensors can transmit graphic data to software that instructs the vehicle to adjust its speed, change lanes, stop, or conduct other basic driving functions.

But traffic laws change from country to country, state to state, and sometimes municipality to municipality. Although certain driving laws are universal, such as obeying the speed limit and traffic signals, others vary, including when to change lanes, whether to yield to pedestrians, or when it’s permissible to make a right turn at a red light. Will a CAV know which side of the road to drive on depending on which country it is in? CAVs will need to recognize and understand when the rules change.

CAVs have a great future, but issues concerning safety, ethics, cybersecurity, transparency, and compliance challenges need to be addressed.

Adoption of standards such as IEEE 2846-2022, “IEEE Standard for Assumptions in Safety-Related Models for Automated Driving Systems,” would be a way to help address some of the challenges.

This article is an edited excerpt of the “Addressing Critical Challenges in Connected Autonomous Vehicles” blog entry published in October.

Reference: https://ift.tt/yK2kLQ5

No comments:

Post a Comment