On 21 April 1962, the Seattle World’s Fair opened to the public. Included in its many exhibits on modern science and the progressive future was this electric desktop orrery. Much like the traditional clockwork orreries of centuries past, this unit showed the motions of the planets and other celestial objects, with an overlay that revealed the moons, stars, and a few comets.

The United States was at the time approaching “peak space.” The previous year, cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin had become the first human to reach outer space, and on 12 September 1962 President Kennedy would announce the United States’ intention to put a man on the moon before the decade’s end. The U.S. government committed US $9 million to help build a NASA-themed science exhibit at the Seattle World’s Fair. The fair’s iconic landmark was the Space Needle.

All in all, it seemed like the ideal place to debut a space-age electric orrery.

What is an orrery?

Traditional orreries were mechanical models of the solar system. These often beautiful and intricate instruments were devised by skilled clockmakers to illustrate how the planets and their moons moved through the solar system. Although the ancient Greeks and Romans had planetarium devices that calculated astronomical positions, it wasn’t until the early 18th century that orreries took their name. Around 1713, the English nobleman Charles Boyle (grandnephew of Robert Boyle, a founder of modern chemistry) commissioned such a device for his son. Boyle was the 4th Earl of Orrery. The name stuck.

This 6-minute documentary, about the restoration of a 1758 grand orrery—so called because it includes the outer planets—is worth watching because it shows the internal gears and clockwork mechanisms:

A predecessor to the orrery was the armillary sphere, which featured a ball representing Earth at its center and stars rotating around it. Armillaries could be used to calculate sunrise and sunset and the length of a day. They had a good run up until the mid-16th century, when on his deathbed Nicolaus Copernicus published De revolutionibus orbium coelestium (On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres) and ushered in the heliocentric model of the solar system. Armillary spheres now make fancy garden ornaments.

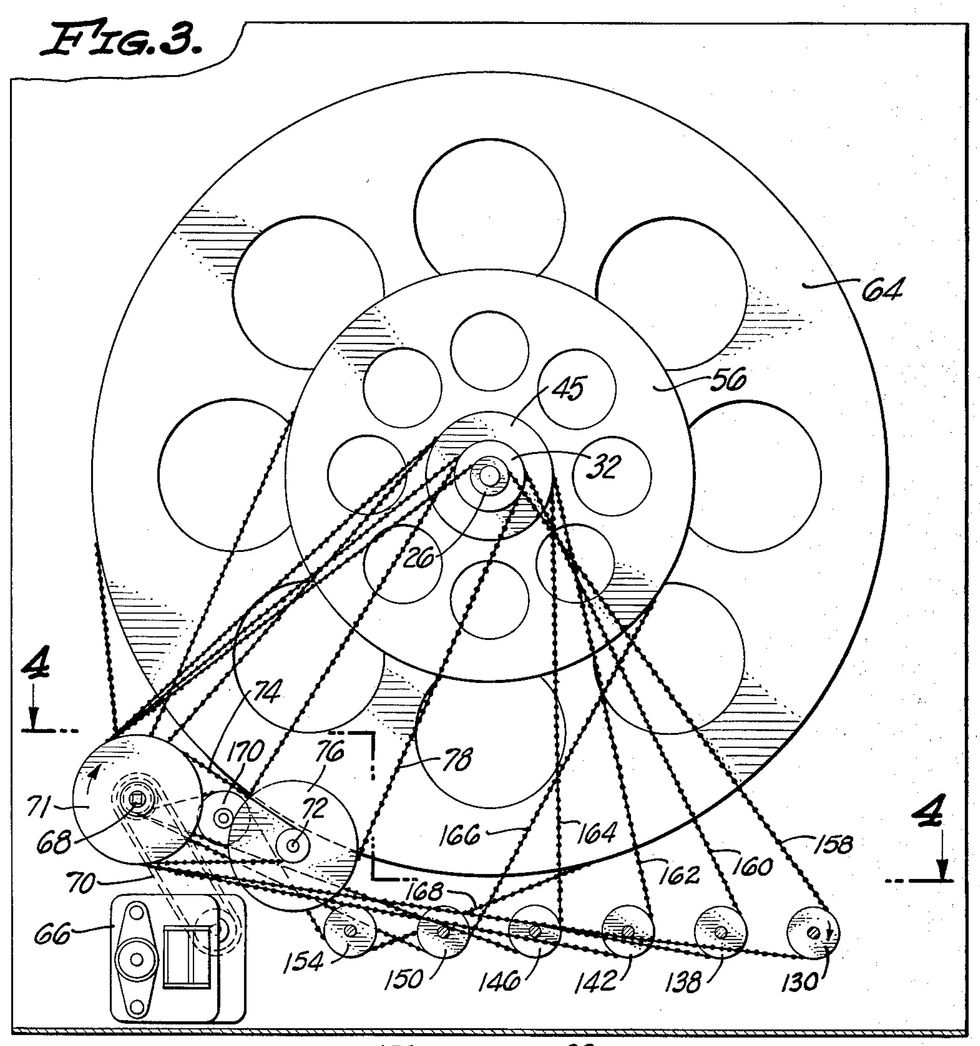

In Clair Omar Musser’s desktop planetarium, each of the nine planets moved on its own shaft and ball chain.U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

In Clair Omar Musser’s desktop planetarium, each of the nine planets moved on its own shaft and ball chain.U.S. Patent and Trademark Office

By the 1950s, the traditional Copernican orrery was in need of an electronic upgrade. Clair Omar Musser, an engineer working for Scientific Space Industries, a subsidiary of Hughes Aircraft, took up the challenge. In his 1958 U.S. patent application for a “new and improved orrery,” Musser mentioned the importance of showing the asteroid belt, in light of growing interest in space travel beyond the moon and Mars. His invention would also improve upon traditional orreries by adding the paths of well-known comets.

A lightbulb representing the sun was at the center of Musser’s orrery, mounted on a central shaft with coterminal tubular shafts on which the nine planets (he included Pluto) rotated at their proportional speeds. A translucent screen had astronomical labels and markings inscribed in phosphorus, visible only when backlit with ultraviolet light. The set of knobs below the screen controlled the illumination of the celestial bodies through variable resistance.

Musser’s original orrery was a hulking machine, standing over 2 meters tall and intended for use in museums and university classrooms. He built the prototype in 1958 during the International Geophysical Year. According to the Planetarium Projector and Science Museum, fewer than 50 units were made, and they sold for approximately $6,000 (about $62,000 today). Musser created the more affordable desktop model shown at top for the Seattle World’s Fair. It stood about 60 centimeters tall, about the size of a TV. (To see the desktop orrery in action, check out the two videos at the bottom of this listing at the Agent Gallery Chicago.)

Who was Clair Omar Musser?

I first stumbled across Musser’s desktop orrery, called the Copernican Planetarium Model 500, during a visit to the Whipple Museum of the History of Science, at the University of Cambridge. I already knew a bit about orreries, and I figured it would be easy to find out more about this one and its creator. I was wrong.

A quick Internet search on Musser returned hundreds of thousands of results, but almost nothing about his engineering work. In fact, after weeks of researching, I still know little more than the three unreferenced lines at the end of his Wikipedia page. At some point in the 1950s, he left a teaching position at Northwestern University, moved to Southern California, and began working for Hughes Aircraft and maybe NASA as well. According to Wikipedia, he also received a doctorate in engineering from Oxford University, although I was unable to track down a copy—or even the title—of his thesis.

None of this would have been so odd, except that prior to joining Hughes Aircraft, Musser had never worked as an engineer. Born in 1901 in Manheim, Pa., and brought up in the Mennonite faith, he switched to engineering in his 50s.

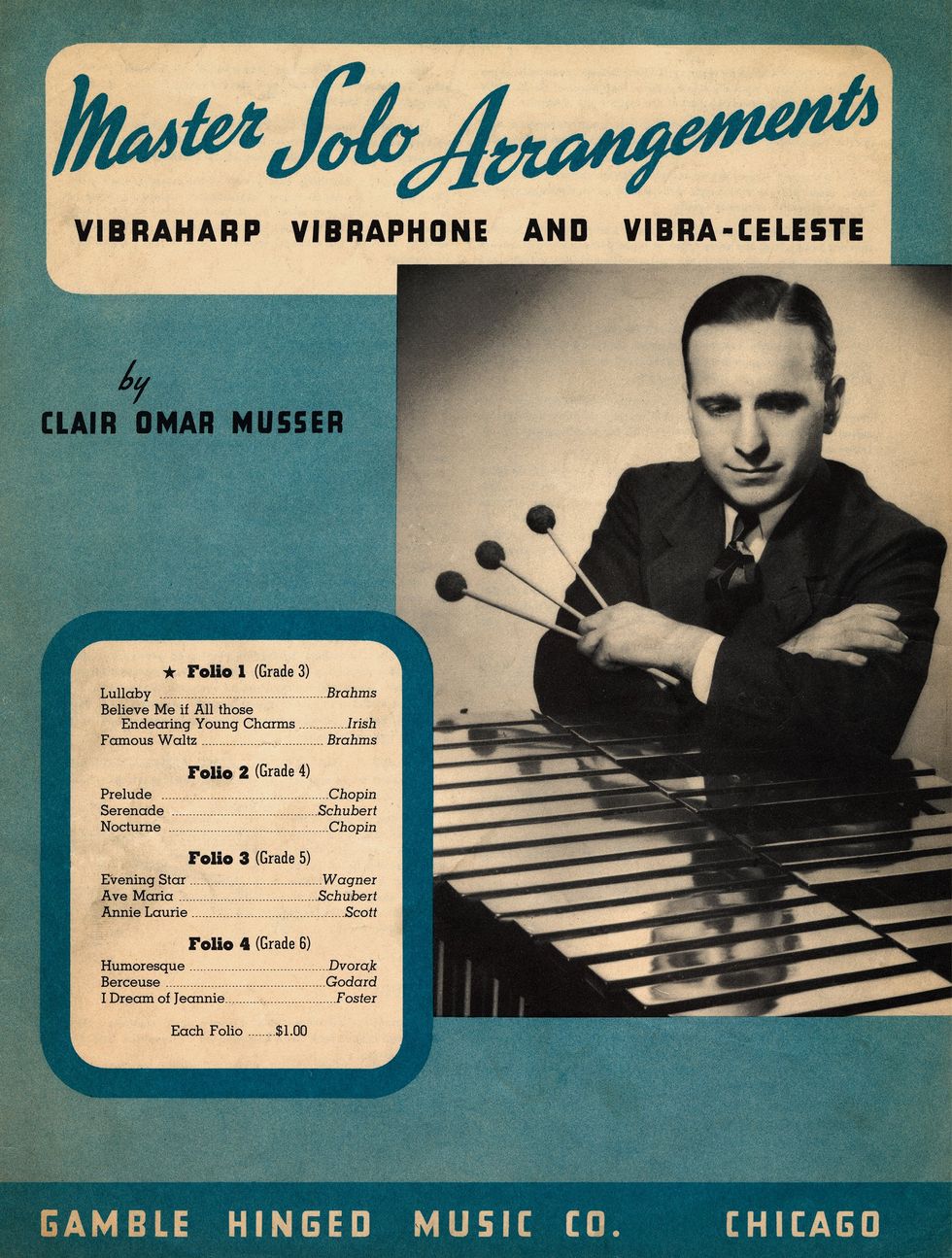

The hundreds of thousands of Internet results on Musser, it turns out, all deal with the first half of his career, as a world-renowned marimba virtuoso and composer. I didn’t know what a marimba is, so I looked it up: It’s a percussion instrument similar to a xylophone, but with a lower range and a warmer, deeper timbre. When I contacted a friend at the University of South Carolina’s School of Music and said I was doing research on Musser, I received an excited “Wow!” Apparently, performing Musser’s etudes for marimba is a rite of passage for percussion majors.

Not only was Musser an amazing performer and composer, he was also a designer of musical instruments. He made innovations in grips, mallets, and techniques, and he held more than 40 international patents on musical instruments. In 1925, he introduced a new instrument, the marimba-celeste, which had a five-octave range that covered both the xylophone’s and the marimba’s registers. In 1929, he organized and directed a 25-piece, all-female marimba ensemble for Paramount Pictures.

For most people, debuting an item at a world’s fair would be a once-in-a-lifetime dream, but Musser’s orrery in Seattle was decidedly second fiddle to his participation in the Chicago Century of Progress Exposition in 1933–34. There, nightly in the Hall of Science, Musser directed a 100-piece marimba orchestra. They played original compositions by Musser, as well as special arrangements of popular pieces. After the fair, he toured Europe with another 100-piece marimba orchestra. They were scheduled to perform for the Silver Jubilee of King George V, for which Musser designed special “coronation” instruments for each member of the orchestra, but their performance was canceled. They did play at the 1935 Brussels World’s Fair and other venues, before returning to the United States and playing at Carnegie Hall. This video captures a concert in Paris:

Not only was Musser an amazing performer and composer, he was also a designer of musical instruments. He made innovations in grips, mallets, and techniques, and he held more than 40 international patents on musical instruments. In 1925, he introduced a new instrument, the marimba-celeste, which had a five-octave range that covered both the xylophone’s and the marimba’s registers. In 1929, he organized and directed a 25-piece, all-female marimba ensemble for Paramount Pictures.

For most people, debuting an item at a world’s fair would be a once-in-a-lifetime dream, but Musser’s orrery in Seattle was decidedly second fiddle to his participation in the Chicago Century of Progress Exposition in 1933–34. There, nightly in the Hall of Science, Musser directed a 100-piece marimba orchestra. They played original compositions by Musser, as well as special arrangements of popular pieces. After the fair, he toured Europe with another 100-piece marimba orchestra. They were scheduled to perform for the Silver Jubilee of King George V, for which Musser designed special “coronation” instruments for each member of the orchestra, but their performance was canceled. They did play at the 1935 Brussels World’s Fair and other venues, before returning to the United States and playing at Carnegie Hall. This video captures a concert in Paris:

What was the Celestaphone?

I don’t know why Musser left the world of music to join Hughes Aircraft. According to the finding aid for the Clair Omar Musser Collection at the Percussive Arts Society, he worked there for only about five years. It seems, though, he had a lifelong fascination with space.

Musser began collecting meteorites in 1936, and his hobby became widely known enough that he received them as gifts. In 1960, for instance, the Soviet Union presented him with a piece of the Sikhote-Alin meteorite. Two years later, the Philippines’ Atomic Energy Commission contributed a siderite, a nickel-iron meteorite.

After four decades of collecting, Musser had amassed 630 kilograms of meteorites. Then, in 1977, he took about half of his collection to a foundry and oversaw the work of melting them down to forge 30 bars of precise sizes and tones. These “meteoric tone bars” became the basis for an extraordinary creation: the Celestaphone.

The Celestaphone is a vibraphone with a 2.5-octave range on a chromatic scale, from the lowest violin G to the 1,000-cycle C above treble clef. It has one sustaining pedal. It now resides at the Rhythm! Discovery Center, in Indianapolis. Here’s a demonstration of the instrument’s ethereal sound:

According to the museum’s research notes on this one-of-a-kind object, it was inspired by Halley’s Comet and Musser’s combined interests in music and space. Musser would have been 8 years old—an impressionable age—when Halley’s Comet came into naked-eye view in 1910. It was the first time the comet had visited since the invention of photography. And on 19 May 1910, Earth actually passed through the comet’s tail. By all accounts, it was a spectacular sight.

Musser lived to see the comet’s return in 1986, although Earth’s positioning with the sun made for some of the worst possible viewing conditions. (My 12-year-old self remembers staring at the night sky and not seeing the comet.)

It’s going too far to ascribe to a comet the power to direct someone’s career, and yet Musser definitely followed his own eccentric orbit. But just as celestial orbits are periodic, music for pitched percussion like the marimba and the Celestaphone often relies on periodic musical phrases. Perhaps Musser’s planetarium, like his impressive corpus of compositions for the marimba, speaks to an enduring fascination with the music of the spheres.

Part of a continuing series looking at historical artifacts that embrace the boundless potential of technology.

An abridged version of this article appears in the October 2023 print issue as “No Ordinary Orrery.”

References

Historians appreciate footnotes and citations in order to track down the original primary source of information. Unfortunately, in the case of Musser (and especially his engineering activities), references are decidedly lacking.

My initial source of information was David Paul Eyler’s 1985 dissertation, The History of Development of the Marimba Ensemble in the United States and its Current Status in College and University Percussion Programs, written as part of his doctorate in musical arts for Louisiana State University.

I reviewed a number of Musser’s patents, for his orreries as well as his musical instruments. I made extensive use of my university’s interlibrary loan service to track down articles from Metronome and the Percussive Arts Society. I also relied on content posted online by museums, including the Whipple Museum of the History of Science, the Rhythm! Discovery Center, and the Planetarium Projector and Science Museum.

In the end, I am still left with more questions than answers about this fascinating man, and no good “go to” biography to recommend for further reading. More research is waiting to be done.

No comments:

Post a Comment