What could you do with an extra limb? Consider a surgeon performing a delicate operation, one that needs her expertise and steady hands—all three of them. As her two biological hands manipulate surgical instruments, a third robotic limb that’s attached to her torso plays a supporting role. Or picture a construction worker who is thankful for his extra robotic hand as it braces the heavy beam he’s fastening into place with his other two hands. Imagine wearing an exoskeleton that would let you handle multiple objects simultaneously, like Spiderman’s Dr. Octopus. Or contemplate the out-there music a composer could write for a pianist who has 12 fingers to spread across the keyboard.

Such scenarios may seem like science fiction, but recent progress in robotics and neuroscience makes extra robotic limbs conceivable with today’s technology. Our research groups at Imperial College London and the University of Freiburg, in Germany, together with partners in the European project NIMA, are now working to figure out whether such augmentation can be realized in practice to extend human abilities. The main questions we’re tackling involve both neuroscience and neurotechnology: Is the human brain capable of controlling additional body parts as effectively as it controls biological parts? And if so, what neural signals can be used for this control?

We think that extra robotic limbs could be a new form of human augmentation, improving people’s abilities on tasks they can already perform as well as expanding their ability to do things they simply cannot do with their natural human bodies. If humans could easily add and control a third arm, or a third leg, or a few more fingers, they would likely use them in tasks and performances that went beyond the scenarios mentioned here, discovering new behaviors that we can’t yet even imagine.

Levels of human augmentation

Robotic limbs have come a long way in recent decades, and some are already used by people to enhance their abilities. Most are operated via a joystick or other hand controls. For example, that’s how workers on manufacturing lines wield mechanical limbs that hold and manipulate components of a product. Similarly, surgeons who perform robotic surgery sit at a console across the room from the patient. While the surgical robot may have four arms tipped with different tools, the surgeon’s hands can control only two of them at a time. Could we give these surgeons the ability to control four tools simultaneously?

Robotic limbs are also used by people who have amputations or paralysis. That includes people in powered wheelchairs controlling a robotic arm with the chair’s joystick and those who are missing limbs controlling a prosthetic by the actions of their remaining muscles. But a truly mind-controlled prosthesis is a rarity.

If humans could easily add and control a third arm, they would likely use them in new behaviors that we can’t yet even imagine.

The pioneers in brain-controlled prosthetics are people with tetraplegia, who are often paralyzed from the neck down. Some of these people have boldly volunteered for clinical trials of brain implants that enable them to control a robotic limb by thought alone, issuing mental commands that cause a robot arm to lift a drink to their lips or help with other tasks of daily life. These systems fall under the category of brain-machine interfaces (BMI). Other volunteers have used BMI technologies to control computer cursors, enabling them to type out messages, browse the Internet, and more. But most of these BMI systems require brain surgery to insert the neural implant and include hardware that protrudes from the skull, making them suitable only for use in the lab.

Augmentation of the human body can be thought of as having three levels. The first level increases an existing characteristic, in the way that, say, a powered exoskeleton can give the wearer super strength. The second level gives a person a new degree of freedom, such as the ability to move a third arm or a sixth finger, but at a cost—if the extra appendage is controlled by a foot pedal, for example, the user sacrifices normal mobility of the foot to operate the control system. The third level of augmentation, and the least mature technologically, gives a user an extra degree of freedom without taking mobility away from any other body part. Such a system would allow people to use their bodies normally by harnessing some unused neural signals to control the robotic limb. That’s the level that we’re exploring in our research.

Deciphering electrical signals from muscles

Third-level human augmentation can be achieved with invasive BMI implants, but for everyday use, we need a noninvasive way to pick up brain commands from outside the skull. For many research groups, that means relying on tried-and-true electroencephalography (EEG) technology, which uses scalp electrodes to pick up brain signals. Our groups are working on that approach, but we are also exploring another method: using electromyography (EMG) signals produced by muscles. We’ve spent more than a decade investigating how EMG electrodes on the skin’s surface can detect electrical signals from the muscles that we can then decode to reveal the commands sent by spinal neurons.

Electrical signals are the language of the nervous system. Throughout the brain and the peripheral nerves, a neuron “fires” when a certain voltage—some tens of millivolts—builds up within the cell and causes an action potential to travel down its axon, releasing neurotransmitters at junctions, or synapses, with other neurons, and potentially triggering those neurons to fire in turn. When such electrical pulses are generated by a motor neuron in the spinal cord, they travel along an axon that reaches all the way to the target muscle, where they cross special synapses to individual muscle fibers and cause them to contract. We can record these electrical signals, which encode the user’s intentions, and use them for a variety of control purposes.

Deciphering the individual neural signals based on what can be read by surface EMG, however, is not a simple task. A typical muscle receives signals from hundreds of spinal neurons. Moreover, each axon branches at the muscle and may connect with a hundred or more individual muscle fibers distributed throughout the muscle. A surface EMG electrode picks up a sampling of this cacophony of pulses.

A breakthrough in noninvasive neural interfaces came with the discovery in 2010 that the signals picked up by high-density EMG, in which tens to hundreds of electrodes are fastened to the skin, can be disentangled, providing information about the commands sent by individual motor neurons in the spine. Such information had previously been obtained only with invasive electrodes in muscles or nerves. Our high-density surface electrodes provide good sampling over multiple locations, enabling us to identify and decode the activity of a relatively large proportion of the spinal motor neurons involved in a task. And we can now do it in real time, which suggests that we can develop noninvasive BMI systems based on signals from the spinal cord.

A typical muscle receives signals from hundreds of spinal neurons.

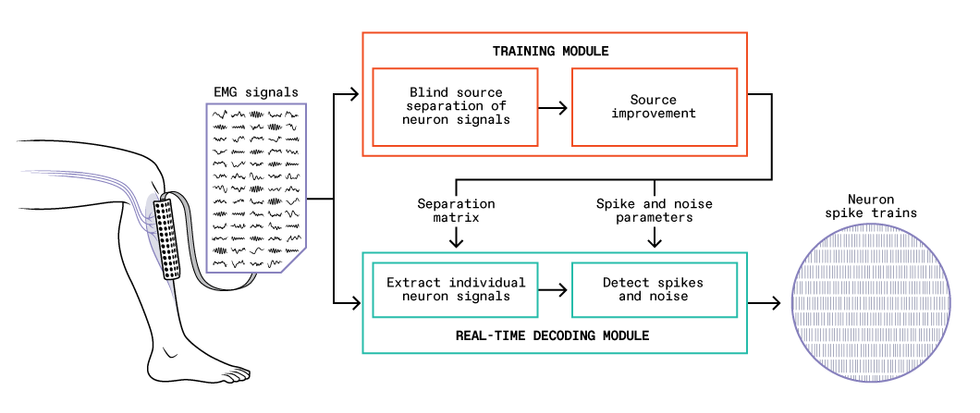

The current version of our system consists of two parts: a training module and a real-time decoding module. To begin, with the EMG electrode grid attached to their skin, the user performs gentle muscle contractions, and we feed the recorded EMG signals into the training module. This module performs the difficult task of identifying the individual motor neuron pulses (also called spikes) that make up the EMG signals. The module analyzes how the EMG signals and the inferred neural spikes are related, which it summarizes in a set of parameters that can then be used with a much simpler mathematical prescription to translate the EMG signals into sequences of spikes from individual neurons.

With these parameters in hand, the decoding module can take new EMG signals and extract the individual motor neuron activity in real time. The training module requires a lot of computation and would be too slow to perform real-time control itself, but it usually has to be run only once each time the EMG electrode grid is fixed in place on a user. By contrast, the decoding algorithm is very efficient, with latencies as low as a few milliseconds, which bodes well for possible self-contained wearable BMI systems. We validated the accuracy of our system by comparing its results with signals obtained concurrently by two invasive EMG electrodes inserted into the user’s muscle.

Exploiting extra bandwidth in neural signals

Developing this real-time method to extract signals from spinal motor neurons was the key to our present work on controlling extra robotic limbs. While studying these neural signals, we noticed that they have, essentially, extra bandwidth. The low-frequency part of the signal (below about 7 hertz) is converted into muscular force, but the signal also has components at higher frequencies, such as those in the beta band at 13 to 30 Hz, which are too high to control a muscle and seem to go unused. We don’t know why the spinal neurons send these higher-frequency signals; perhaps the redundancy is a buffer in case of new conditions that require adaptation. Whatever the reason, humans evolved a nervous system in which the signal that comes out of the spinal cord has much richer information than is needed to command a muscle.

That discovery set us thinking about what could be done with the spare frequencies. In particular, we wondered if we could take that extraneous neural information and use it to control a robotic limb. But we didn’t know if people would be able to voluntarily control this part of the signal separately from the part they used to control their muscles. So we designed an experiment to find out.

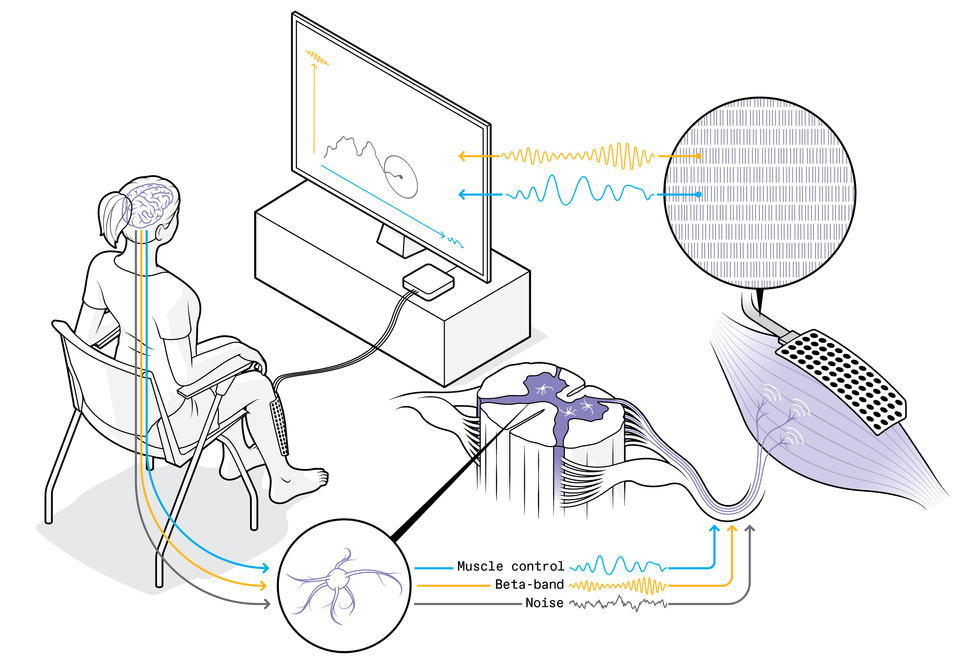

In our first proof-of-concept experiment, volunteers tried to use their spare neural capacity to control computer cursors. The setup was simple, though the neural mechanism and the algorithms involved were sophisticated. Each volunteer sat in front of a screen, and we placed an EMG system on their leg, with 64 electrodes in a 4-by-10-centimeter patch stuck to their shin over the tibialis anterior muscle, which flexes the foot upward when it contracts. The tibialis has been a workhorse for our experiments: It occupies a large area close to the skin, and its muscle fibers are oriented along the leg, which together make it ideal for decoding the activity of spinal motor neurons that innervate it.

These are some results from the experiment in which low- and high-frequency neural signals, respectively, controlled horizontal and vertical motion of a computer cursor. Colored ellipses (with plus signs at centers) show the target areas. The top three diagrams show the trajectories (each one starting at the lower left) achieved for each target across three trials by one user. At bottom, dots indicate the positions achieved across many trials and users. Colored crosses mark the mean positions and the range of results for each target.Source: M. Bräcklein et al., Journal of Neural Engineering

These are some results from the experiment in which low- and high-frequency neural signals, respectively, controlled horizontal and vertical motion of a computer cursor. Colored ellipses (with plus signs at centers) show the target areas. The top three diagrams show the trajectories (each one starting at the lower left) achieved for each target across three trials by one user. At bottom, dots indicate the positions achieved across many trials and users. Colored crosses mark the mean positions and the range of results for each target.Source: M. Bräcklein et al., Journal of Neural Engineering

We asked our volunteers to steadily contract the tibialis, essentially holding it tense, and throughout the experiment we looked at the variations within the extracted neural signals. We separated these signals into the low frequencies that controlled the muscle contraction and spare frequencies at about 20 Hz in the beta band, and we linked these two components respectively to the horizontal and vertical control of a cursor on a computer screen. We asked the volunteers to try to move the cursor around the screen, reaching all parts of the space, but we didn’t, and indeed couldn’t, explain to them how to do that. They had to rely on the visual feedback of the cursor’s position and let their brains figure out how to make it move.

Remarkably, without knowing exactly what they were doing, these volunteers mastered the task within minutes, zipping the cursor around the screen, albeit shakily. Beginning with one neural command signal—contract the tibialis anterior muscle—they were learning to develop a second signal to control the computer cursor’s vertical motion, independently from the muscle control (which directed the cursor’s horizontal motion). We were surprised and excited by how easily they achieved this big first step toward finding a neural control channel separate from natural motor tasks. But we also saw that the control was not accurate enough for practical use. Our next step will be to see if more accurate signals can be obtained and if people can use them to control a robotic limb while also performing independent natural movements.

We are also interested in understanding more about how the brain performs feats like the cursor control. In a recent study using a variation of the cursor task, we concurrently used EEG to see what was happening in the user’s brain, particularly in the area associated with the voluntary control of movements. We were excited to discover that the changes happening to the extra beta-band neural signals arriving at the muscles were tightly related to similar changes at the brain level. As mentioned, the beta neural signals remain something of a mystery since they play no known role in controlling muscles, and it isn’t even clear where they originate. Our result suggests that our volunteers were learning to modulate brain activity that was sent down to the muscles as beta signals. This important finding is helping us unravel the potential mechanisms behind these beta signals.

Meanwhile, at Imperial College London we have set up a system for testing these new technologies with extra robotic limbs, which we call the MUlti-limb Virtual Environment, or MUVE. Among other capabilities, MUVE will enable users to work with as many as four lightweight wearable robotic arms in scenarios simulated by virtual reality. We plan to make the system open for use by other researchers worldwide.

Next steps in human augmentation

Connecting our control technology to a robotic arm or other external device is a natural next step, and we’re actively pursuing that goal. The real challenge, however, will not be attaching the hardware, but rather identifying multiple sources of control that are accurate enough to perform complex and precise actions with the robotic body parts.

We are also investigating how the technology will affect the neural processes of the people who use it. For example, what will happen after someone has six months of experience using an extra robotic arm? Would the natural plasticity of the brain enable them to adapt and gain a more intuitive kind of control? A person born with six-fingered hands can have fully developed brain regions dedicated to controlling the extra digits, leading to exceptional abilities of manipulation. Could a user of our system develop comparable dexterity over time? We’re also wondering how much cognitive load will be involved in controlling an extra limb. If people can direct such a limb only when they’re focusing intently on it in a lab setting, this technology may not be useful. However, if a user can casually employ an extra hand while doing an everyday task like making a sandwich, then that would mean the technology is suited for routine use.

Whatever the reason, humans evolved a nervous system in which the signal that comes out of the spinal cord has much richer information than is needed to command a muscle.

Other research groups are pursuing the same neuroscience questions. Some are experimenting with control mechanisms involving either scalp-based EEG or neural implants, while others are working on muscle signals. It is early days for movement augmentation, and researchers around the world have just begun to address the most fundamental questions of this emerging field.

Two practical questions stand out: Can we achieve neural control of extra robotic limbs concurrently with natural movement, and can the system work without the user’s exclusive concentration? If the answer to either of these questions is no, we won’t have a practical technology, but we’ll still have an interesting new tool for research into the neuroscience of motor control. If the answer to both questions is yes, we may be ready to enter a new era of human augmentation. For now, our (biological) fingers are crossed.

Reference: https://ift.tt/KIS1kEp A training module [orange] takes an initial batch of EMG signals read by the electrode array [left], determines how to extract signals of individual neurons, and summarizes the process mathematically as a separation matrix and other parameters. With these tools, the real-time decoding module [green] can efficiently extract individual neurons’ sequences of spikes, or “spike trains” [right], from an ongoing stream of EMG signals. Chris Philpot

A training module [orange] takes an initial batch of EMG signals read by the electrode array [left], determines how to extract signals of individual neurons, and summarizes the process mathematically as a separation matrix and other parameters. With these tools, the real-time decoding module [green] can efficiently extract individual neurons’ sequences of spikes, or “spike trains” [right], from an ongoing stream of EMG signals. Chris Philpot A volunteer exploits unused neural bandwidth to direct the motion of a cursor on the screen in front of her. Neural signals pass from her brain, through spinal neurons, to the muscle in her shin, where they are read by an electromyography (EMG) electrode array on her leg and deciphered in real time. These signals include low-frequency components [blue] that control muscle contractions, higher frequencies [beta band, yellow] with no known biological purpose, and noise [gray]. Chris Philpot; Source:

A volunteer exploits unused neural bandwidth to direct the motion of a cursor on the screen in front of her. Neural signals pass from her brain, through spinal neurons, to the muscle in her shin, where they are read by an electromyography (EMG) electrode array on her leg and deciphered in real time. These signals include low-frequency components [blue] that control muscle contractions, higher frequencies [beta band, yellow] with no known biological purpose, and noise [gray]. Chris Philpot; Source:

No comments:

Post a Comment