The future of human habitation in the sea is taking shape in an abandoned quarry on the border of Wales and England. There, the ocean-exploration organization Deep has embarked on a multiyear quest to enable scientists to live on the seafloor at depths up to 200 meters for weeks, months, and possibly even years.

“Aquarius Reef Base in St. Croix was the last installed habitat back in 1987, and there hasn’t been much ground broken in about 40 years,” says Kirk Krack, human diver performance lead at Deep. “We’re trying to bring ocean science and engineering into the 21st century.”

Deep’s agenda has a major milestone this year—the development and testing of a small, modular habitat called Vanguard. This transportable, pressurized underwater shelter, capable of housing up to three divers for periods ranging up to a week or so, will be a stepping stone to a more permanent modular habitat system—known as Sentinel—that is set to launch in 2027. “By 2030, we hope to see a permanent human presence in the ocean,” says Krack. All of this is now possible thanks to an advanced 3D printing-welding approach that can print these large habitation structures.

How would such a presence benefit marine science? Krack runs the numbers for me: “With current diving at 150 to 200 meters, you can only get 10 minutes of work completed, followed by 6 hours of decompression. With our underwater habitats we’ll be able to do seven years’ worth of work in 30 days with shorter decompression time. More than 90 percent of the ocean’s biodiversity lives within 200 meters’ depth and at the shorelines, and we only know about 20 percent of it.” Understanding these undersea ecosystems and environments is a crucial piece of the climate puzzle, he adds: The oceans absorb nearly a quarter of human-caused carbon dioxide and roughly 90 percent of the excess heat generated by human activity.

Underwater Living Gets the Green Light This Year

Deep is looking to build an underwater life-support infrastructure that features not just modular habitats but also training programs for the scientists who will use them. Long-term habitation underwater involves a specialized type of activity called saturation diving, so named because the diver’s tissues become saturated with gases, such as nitrogen or helium. It has been used for decades in the offshore oil and gas sectors but is uncommon in scientific diving, outside of the relatively small number of researchers fortunate enough to have spent time in Aquarius. Deep wants to make it a standard practice for undersea researchers.

The first rung in that ladder is Vanguard, a rapidly deployable, expedition-style underwater habitat the size of a shipping container that can be transported and supplied by a ship and house three people down to depths of about 100 meters. It is set to be tested in a quarry outside of Chepstow, Wales, in the first quarter of 2025.

The Vanguard habitat, seen here in an illustrator’s rendering, will be small enough to be transportable and yet capable of supporting three people at a maximum depth of 100 meters.Deep

The Vanguard habitat, seen here in an illustrator’s rendering, will be small enough to be transportable and yet capable of supporting three people at a maximum depth of 100 meters.Deep

The plan is to be able to deploy Vanguard wherever it’s needed for a week or so. Divers will be able to work for hours on the seabed before retiring to the module for meals and rest.

One of the novel features of Vanguard is its extraordinary flexibility when it comes to power. There are currently three options: When deployed close to shore, it can connect by cable to an onshore distribution center using local renewables. Farther out at sea, it could use supply from floating renewable-energy farms and fuel cells that would feed Vanguard via an umbilical link, or it could be supplied by an underwater energy-storage system that contains multiple batteries that can be charged, retrieved, and redeployed via subsea cables.

The breathing gases will be housed in external tanks on the seabed and contain a mix of oxygen and helium that will depend on the depth. In the event of an emergency, saturated divers won’t be able to swim to the surface without suffering a life-threatening case of decompression illness. So, Vanguard, as well as the future Sentinel, will also have backup power sufficient to provide 96 hours of life support, in an external, adjacent pod on the seafloor.

Data gathered from Vanguard this year will help pave the way for Sentinel, which will be made up of pods of different sizes and capabilities. These pods will even be capable of being set to different internal pressures, so that different sections can perform different functions. For example, the labs could be at the local bathymetric pressure for analyzing samples in their natural environment, but alongside those a 1-atmosphere chamber could be set up where submersibles could dock and visitors could observe the habitat without needing to equalize with the local pressure.

As Deep sees it, a typical configuration would house six people—each with their own bedroom and bathroom. It would also have a suite of scientific equipment including full wet labs to perform genetic analyses, saving days by not having to transport samples to a topside lab for analysis.

“By 2030, we hope to see a permanent human presence in the ocean,” says one of the project’s principals

A Sentinel configuration is designed to go for a month before needing a resupply. Gases will be topped off via an umbilical link from a surface buoy, and food, water, and other supplies would be brought down during planned crew changes every 28 days.

But people will be able to live in Sentinel for months, if not years. “Once you’re saturated, it doesn’t matter if you’re there for six days or six years, but most people will be there for 28 days due to crew changes,” says Krack.

Where 3D Printing and Welding Meet

It’s a very ambitious vision, and Deep has concluded that it can be achieved only with advanced manufacturing techniques. Deep’s manufacturing arm, Deep Manufacturing Labs (DML), has come up with an innovative approach for building the pressure hulls of the habitat modules. It’s using robots to combine metal additive manufacturing with welding in a process known as wire-arc additive manufacturing. With these robots, metal layers are built up as they would be in 3D printing, but the layers are fused together via welding using a metal-inert-gas torch.

At Deep’s base of operations at a former quarry in Tidenham, England, resources include two Triton 3300/3 MK II submarines. One of them is seen here at Deep’s floating “island” dock in the quarry. Deep

At Deep’s base of operations at a former quarry in Tidenham, England, resources include two Triton 3300/3 MK II submarines. One of them is seen here at Deep’s floating “island” dock in the quarry. Deep

During a tour of the DML, Harry Thompson, advanced manufacturing engineering lead, says, “We sit in a gray area between welding and additive process, so we’re following welding rules, but for pressure vessels we [also] follow a stress-relieving process that is applicable for an additive component. We’re also testing all the parts with nondestructive testing.”

Each of the robot arms has an operating range of 2.8 by 3.2 meters, but DML has boosted this area by means of a concept it calls Hexbot. It’s based on six robotic arms programmed to work in unison to create habitat hulls with a diameter of up to 6.1 meters. The biggest challenge with creating the hulls is managing the heat during the additive process to keep the parts from deforming as they are created. For this, DML is relying on the use of heat-tolerant steels and on very precisely optimized process parameters.

Engineering Challenges for Long-Term Habitation

Besides manufacturing, there are other challenges that are unique to the tricky business of keeping people happy and alive 200 meters underwater. One of the most fascinating of these revolves around helium. Because of its narcotic effect at high pressure, nitrogen shouldn’t be breathed by humans at depths below about 60 meters. So, at 200 meters, the breathing mix in the habitat will be 2 percent oxygen and 98 percent helium. But because of its very high thermal conductivity, “we need to heat helium to 31–32 °C to get a normal 21–22 °C internal temperature environment,” says Rick Goddard, director of engineering at Deep. “This creates a humid atmosphere, so porous materials become a breeding ground for mold”.

There are a host of other materials-related challenges, too. The materials can’t emit gases, and they must be acoustically insulating, lightweight, and structurally sound at high pressures.

Deep’s proving grounds are a former quarry in Tidenham, England, that has a maximum depth of 80 meters. Deep

Deep’s proving grounds are a former quarry in Tidenham, England, that has a maximum depth of 80 meters. Deep

There are also many electrical challenges. “Helium breaks certain electrical components with a high degree of certainty,” says Goddard. “We’ve had to pull devices to pieces, change chips, change [printed circuit boards], and even design our own PCBs that don’t off-gas.”

The electrical system will also have to accommodate an energy mix with such varied sources as floating solar farms and fuel cells on a surface buoy. Energy-storage devices present major electrical engineering challenges: Helium seeps into capacitors and can destroy them when it tries to escape during decompression. Batteries, too, develop problems at high pressure, so they will have to be housed outside the habitat in 1-atmosphere pressure vessels or in oil-filled blocks that prevent a differential pressure inside.

Is it Possible to Live in the Ocean for Months or Years?

When you’re trying to be the SpaceX of the ocean, questions are naturally going to fly about the feasibility of such an ambition. How likely is it that Deep can follow through? At least one top authority, John Clarke, is a believer. “I’ve been astounded by the quality of the engineering methods and expertise applied to the problems at hand and I am enthusiastic about how DEEP is applying new technology,” says Clarke, who was lead scientist of the U.S. Navy Experimental Diving Unit. “They are advancing well beyond expectations…. I gladly endorse Deep in their quest to expand humankind’s embrace of the sea.”

Reference: https://ift.tt/cs54XlA David Plunkert

David Plunkert Gary Marcus and Reid Southen via Midjourney

Gary Marcus and Reid Southen via Midjourney Getty Images

Getty Images Alamy

Alamy Mike McQuade

Mike McQuade IEEE Spectrum

IEEE Spectrum iStock

iStock Edd Gent

Edd Gent Mike Kemp/Getty Images

Mike Kemp/Getty Images The Voorhes

The Voorhes

Susumu Noda

Susumu Noda Intel

Intel Chris McKenney/Georgia Institute of Technology

Chris McKenney/Georgia Institute of Technology Intel

Intel David Plunkert

David Plunkert iStock

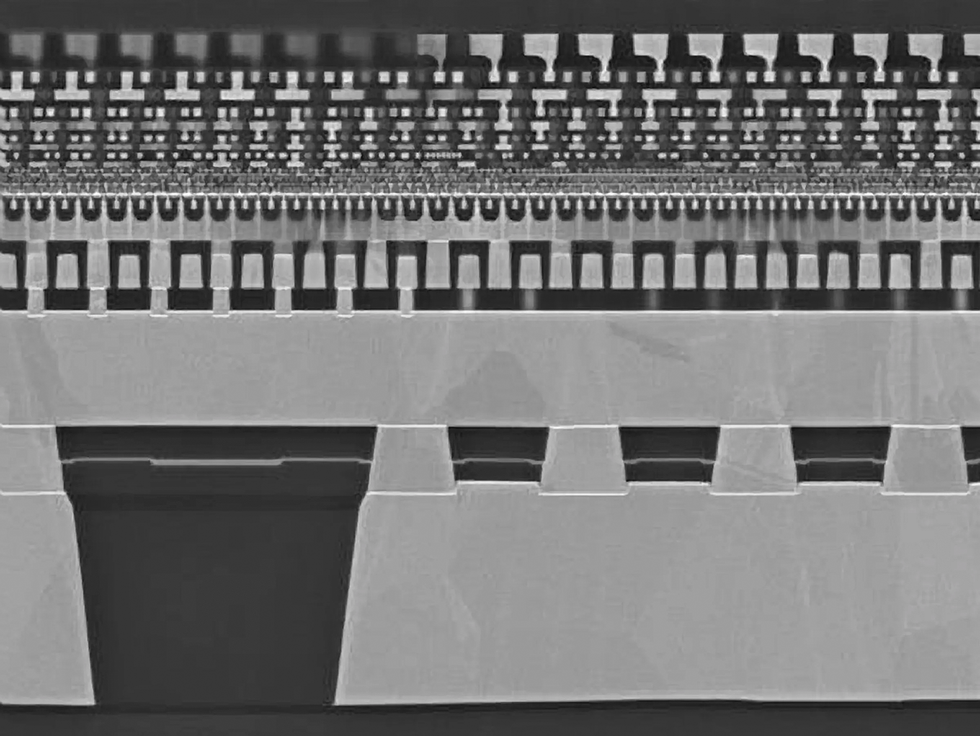

iStock imec

imec KEK

KEK Tesla

Tesla

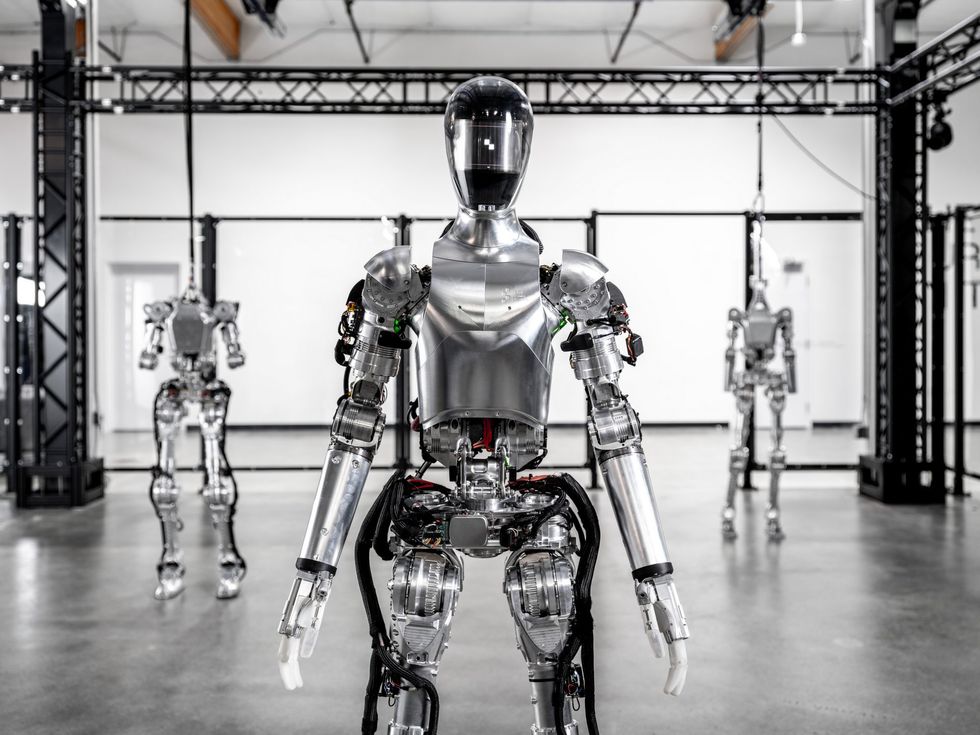

Figure

Figure Boston Dynamics

Boston Dynamics Boston Dynamics

Boston Dynamics Nvidia

Nvidia Evan Ackerman

Evan Ackerman Machina Labs

Machina Labs JPL-Caltech/ASU/NASA

JPL-Caltech/ASU/NASA

VCG/Getty Images

VCG/Getty Images Mittleman Group/Brown University

Mittleman Group/Brown University Andriy Onufriyenko/Getty Images

Andriy Onufriyenko/Getty Images Ian Forsyth/Bloomberg/Getty Images

Ian Forsyth/Bloomberg/Getty Images Morse Micro

Morse Micro Harald Ritsch/Science Source

Harald Ritsch/Science Source IEEE Spectrum

IEEE Spectrum JTower

JTower Huber & Starke/Getty Images

Huber & Starke/Getty Images iStock

iStock