James Weldon Johnson’s hymn “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” adopted by African Americans as the unofficial “Negro National Anthem,” includes the line, “We have come over a way that with tears has been watered,” which sums up how Black Americans have found ways to thrive under conditions they weren’t meant to survive. Emblematic of the hope, faith, perseverance, and drive to overcome systemic legal and social barriers the song encapsulates is the life of self-taught technical genius Lewis H. Latimer. By the time he died nearly 100 years ago, he had been awarded 10 U.S. patents, including ones for an improved lightbulb filament, an early version of what we would today call an air conditioner, and an improved restroom facility for trains. Along the way, he molded himself into a leader in industry and his community, and became a living, breathing rebuke to the assertion that Blacks were inherently inferior to Whites.

Before failing eyesight forced him into retirement in 1922 at age 74, he had proved himself the definition of a renaissance man. His career highlights include being instrumental in Alexander Graham Bell being awarded the patent for the telephone in 1876, being named a member of the inaugural group of technologists known as “Edison Pioneers,” and developing the filament that turned Edison’s electric lightbulb from an expensive novelty to a reliable, long-lasting commodity. His mechanical drawings were so exquisite that he raised drafting to the level of visual art. Meanwhile, he wrote poetry, played the flute, became a renowned public intellectual writing about the confluence of art and science, and even taught himself to speak French well enough to supervise an electrical lighting installation working with francophones in Montreal.

A 70-year-old Latimer [in the foreground seated at the right side of the table] was photographed along with other Edison Pioneers in 1918.Lewis Latimer House/Alamy

A 70-year-old Latimer [in the foreground seated at the right side of the table] was photographed along with other Edison Pioneers in 1918.Lewis Latimer House/Alamy

Unlike his Black contemporary Granville T. Woods , whose fierce independence left him with few resources and helpful contacts, Latimer inserted himself into positions where he used his unrivaled experience and expertise to elevate others. He advanced himself by helping to preserve the legacies of other inventors, many of whom are regarded as the leading innovators of their time. What would the name Alexander Graham Bell mean to us today if Lewis Latimer wasn’t there providing the invaluable assistance that helped Bell win the race to patent the telephone? The same could be asked regarding Edison’s association with the incandescent lightbulb because Latimer performed the unsung tasks of solidifying the enforceability of Edison General Electric’s patent holdings and putting a league of upstart indoor lighting competitors out of business. Latimer literally wrote the book on electric lighting at Edison’s urging: Incandescent Electric Lighting: A Practical Description of the Edison System was published in 1890 by the Van Nostrand Company, a leading publisher of trade, technical, and scientific books in the 19th century.

There’s also the matter of Latimer’s own indispensable invention: a process for producing an improved carbon filament for bulbs that made them longer lasting, cheaper, and accessible by the masses just in time for the large-scale electrification efforts in the United States.

Latimer’s Troubled Beginnings

Latimer, the fourth of four children of George and Rebecca Latimer, was born in Chelsea, Mass., on 4 September 1848. Both parents were fugitives, having finally escaped enslavement in Virginia after several unsuccessful attempts. As fate would have it, George was spotted in Boston one day by an acquaintance of the human trafficker who had once held him in bondage. Before Latimer could be returned to Virginia to the control of his former enslaver, a league of abolitionists including Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison rallied around him, making him a cause célèbre. A Black Boston minister paid to free him. But the existential dread associated with being a Black man without documents certifying that he was free became more pitched when the U.S. Supreme Court, in the 1857 Dred Scott v. Sandford decision, ruled that an enslaved person was not made free by entering a state whose laws forbid slavery. Understanding that Massachusetts, a “free” state, was not the safe haven he once imagined it to be, George Latimer chose to leave Rebecca and their four children rather than see his precarious legal status put them in the crosshairs of mercenary slave catchers.

Latimer molded himself into a leader in industry and his community, and became a living, breathing rebuke to the assertion that Blacks were inherently inferior to Whites.

At that point, his son Lewis was 10 years old. Despite the hole blasted in the family dynamic, young Lewis remained an excellent student until his academic career was cut short by the loss of George’s income. Out of sheer desperation, his mother split up the family, sending Lewis’ sister to live with relatives and the three Latimer boys to a state-run school where they were trained in farming.

It was, no doubt, lingering resentment over the difficult choices forced upon his parents that led a 16-year-old Lewis to forge identity papers so he could enlist in the U.S. Navy in 1864. He served as a landsman, the Navy’s lowest rank at the time, on the gunboat USS Massasoit during the height of the Civil War. When the war ended in 1865, he was honorably discharged. He returned to Boston, reunited with his mother, and got a job as an “office boy” at a patent law office with a salary of $3.00 a week.

How Latimer Got His Start

Ever the autodidact, Latimer paid close attention to how the draftsmen at the office produced their drawings. Then, at night, he read books on technical drawing and reproduced sketches he had seen at the office. Before long, he had gained enough expertise to feel confident in approaching his employers about a new role at the firm. Right before their eyes, Latimer produced a set of patent sketches that were so impressive, he was soon promoted to draftsman, with a salary of $20.00 a week.

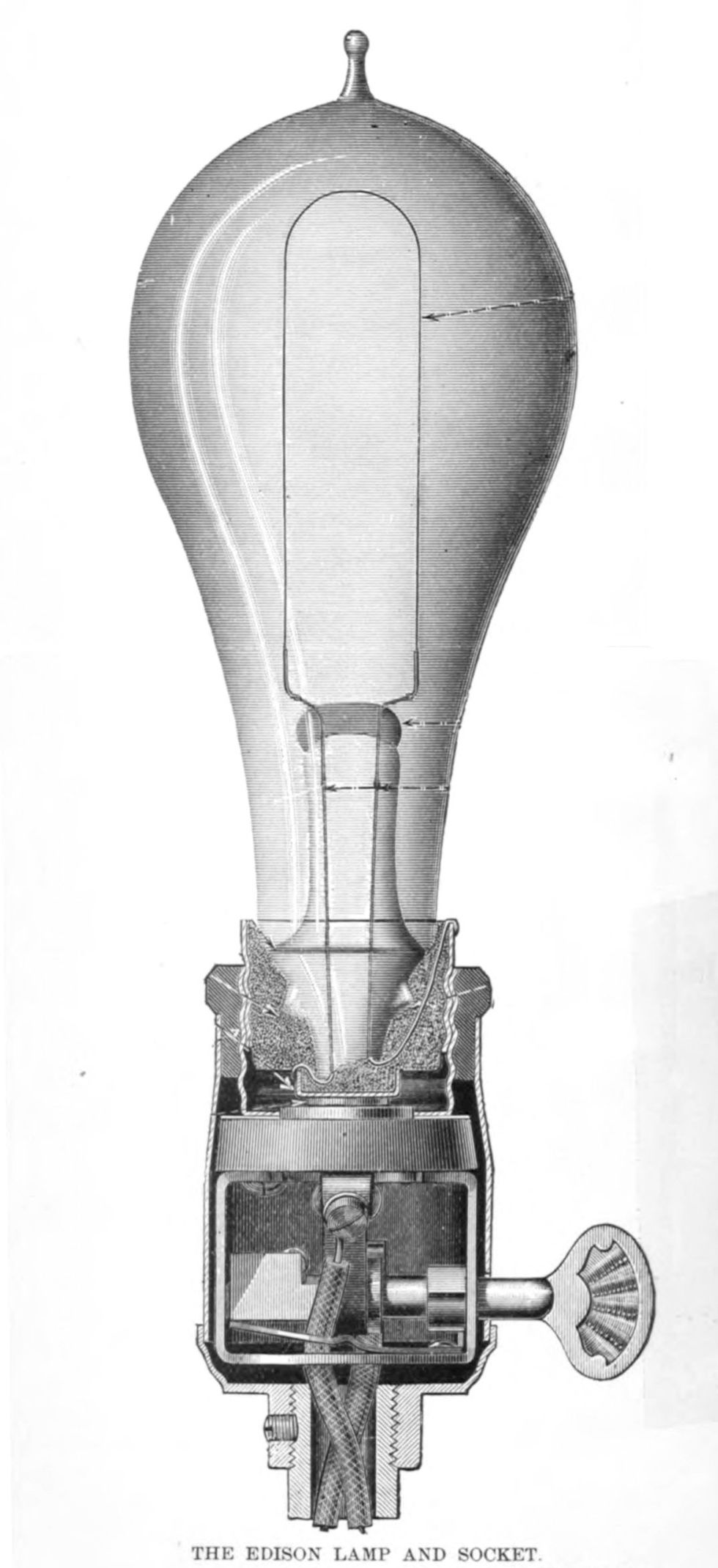

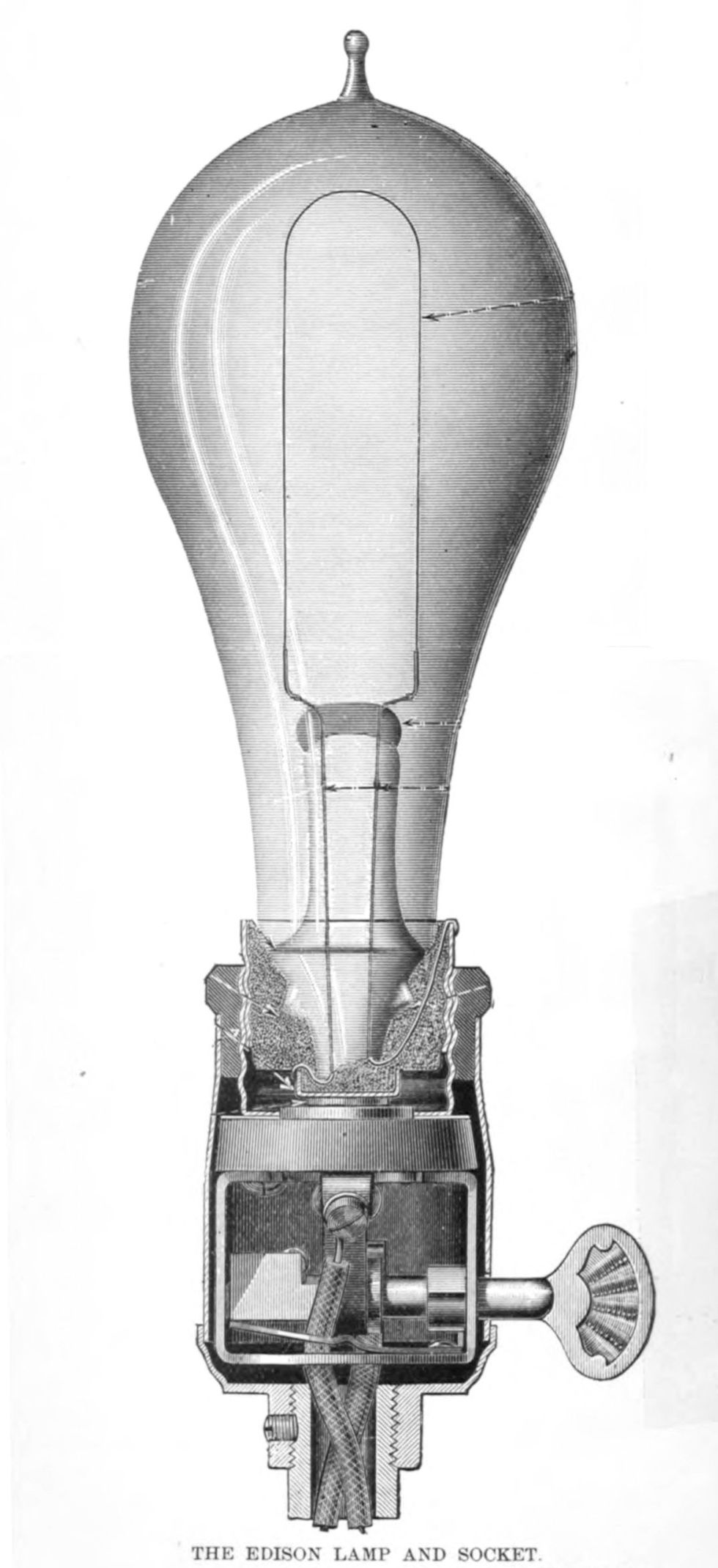

This highly detailed mechanical drawing of an Edison lamp appeared in Latimer’s 1890 book “Incandescent Electric Lighting.”Lewis Latimer/Google

This highly detailed mechanical drawing of an Edison lamp appeared in Latimer’s 1890 book “Incandescent Electric Lighting.”Lewis Latimer/Google

His exquisite patent drawings and keen understanding of how to translate technological ideas into schematics on the printed page were so highly regarded that when Alexander Graham Bell retained the firm to help him put together his patent application for the telephone, Latimer was assigned to do the work. According to historians at the Latimer House Museum in Queens, N.Y., “Latimer helped to develop a more efficient transmitter that improved the quality of the [device's] sound, and his drawings were crucial for securing the telephone patent.”

In 1879, a then-married Latimer moved with his wife Mary, his mother, and his brother William to Bridgeport, Connecticut, on the advice of his sister Margaret. She lived there, as did their brother George, in a section of town called “Little Liberia” that had been founded nearly a century earlier by free Blacks.

In what could only be described as a stroke of luck, Latimer was working as a draftsman at a machine shop in Bridgeport when Hiram Maxim, who would go on to invent the machine gun, came in one day. Maxim was shocked to see a Black man performing something other than menial duties. Upon further investigation, Maxim realized he had stumbled upon the person who could help him advance his own interests in the nascent field of electric lighting.

Maxim hired Latimer as assistant manager and draftsman at his United States Electric Lighting Company, an early rival of Edison General Electric. That was where Latimer developed the invention for which he is most noted—an improved process for producing carbon filaments for lightbulbs that rendered them much more resilient. He even mastered the glassblowing techniques then used to produce lightbulbs.

Stumbling blocks to Latimer revealed themselves to be stepping stones.

Latimer’s mastery of the entire electric lighting process was put on full display in 1881 when Maxim dispatched him to England to oversee the setup and operation of an electric lamp factory for the Maxim company’s partnership there. In only nine months—despite staunch resistance from the British workers to the idea of being trained and supervised by a Black man—Latimer succeeded in getting the electric lighting factory up and running.

At the end of that project, which also spelled the end of his contract with the Maxim Lighting Company, he returned to the United States looking for work. Despite the clear demonstration of his managerial prowess and unsurpassed technical know-how, his career hit rocky shoals. He bounced around, with short, inconsistent stints at fledgling electric lighting companies. He supplemented his much-reduced income by hanging wallpaper—the trade he’d learned from his father during his childhood.

Eventually, these stumbling blocks revealed themselves to be stepping stones. Over the course of Latimer’s many stops, he had come to know nearly all the early lighting companies and their principals. So, he was a natural choice when Edison General Electric’s legal department was looking for someone to speak for the company in a spate of patent interference cases. He was hired in 1888 and served as lead witness for Edison General Electric in court. This was remarkable, because in the 19th century, Black people were routinely said to have no standing in U.S. courts—whether as petitioners, witnesses, or members of juries.

A Man Apart

Latimer was such an exception to the web of unwritten and codified rules meant to assign Blacks to a permanent underclass, he often found it difficult to conceptualize just how far removed his experiences were from those of his Black contemporaries. By the time he began working for Edison, notes Rayon Fouché in his 2003 book Black Inventors in the Age of Segregation, Latimer had “...limited connection with the everyday existence of Black people in America.” He believed that with his achievements, says Fouché, he had purchased entry to “a raceless social, political, and cultural world.” What’s more, he was convinced, despite the Jim Crow laws that circumscribed the legal and civil rights of most Black people, that the route he had taken to personal success was navigable by anyone.

The Latimer House Museum’s collection includes a lightbulb featuring one of its namesake’s inventions—a filament that improved the performance and lifespan of incandescent bulbs.Alamy

The Latimer House Museum’s collection includes a lightbulb featuring one of its namesake’s inventions—a filament that improved the performance and lifespan of incandescent bulbs.Alamy

In a piece of personal correspondence with Booker T. Washington in 1904, Latimer expressed his support for Washington’s view that Blacks could acquire full citizenship rights in the United States by essentially remaking themselves, to whatever extent possible, in the image of Whites. Referring to a letter Washington had written to the Montgomery Adviser in which the Tuskegee University founder said, “Every revised constitution throughout the Southern States has put a premium on intelligence, ownership of property, thrift, and character.” Latimer weighed in with a hearty endorsement of this viewpoint (which would today be called respectability politics) in no small part because he was a paragon of these virtues. “For Latimer,” Fouché wrote, “freedom was not a God-given right, but an earned privilege.” Latimer saw himself as an exemplar of what succeeding generations of African Americans could aspire to.

Of the four cardinal attributes he saw as the keys to respectability in “civilized” society, he is said to have had taken immense pride in the fact that he owned his own home at a time when the average person, White or Black, could not afford such a purchase.

As part of the effort to keep his memory and legacy alive, the house in Queens, New York, in which he resided for the final 10 years of his life has been restored and declared a historical landmark. It now serves as a museum dedicated to teaching about this person who Mary Ann Hellrigel , institutional historian and archivist at the IEEE History Center and advisory board member at the Latimer House Museum, describes as “the most prominent African American draftsman and inventor in early electric light, heat, and power technology.”

The fact that Edison, Tesla, and others of that ilk became so well known “is not [because they were] brighter than Latimer,” says Hellrigel. What they had over him was support and business infrastructure that eventually made them household names. Edison, in particular, “understood the invention business,” says Hellrigel. “He built up a team of reliable lab workers, office workers, and sales agents, and he knew that in order to support this infrastructure… he needed to keep marketing inventions to make money.”

Latimer viewed his career through a different lens than Edison did, says Hellrigel. “He knew that he needed to make money as the draftsman and patent expert in electric lighting,” she says. “Even when he went out on his own, he took on the role of patent consultant.” To the end, he was helping other inventors get their ideas out of their heads and into the world. In doing so, he was being careful to limit the risks that might plunge him once again into poverty. Finding his niche and establishing himself there is part of what Fouché means when he says the most interesting thing he discovered about Latimer and other Black inventors he’s researched was “how shrewd, and careful, and savvy these Black inventors were.”

Reference: https://ift.tt/V9JoMsC

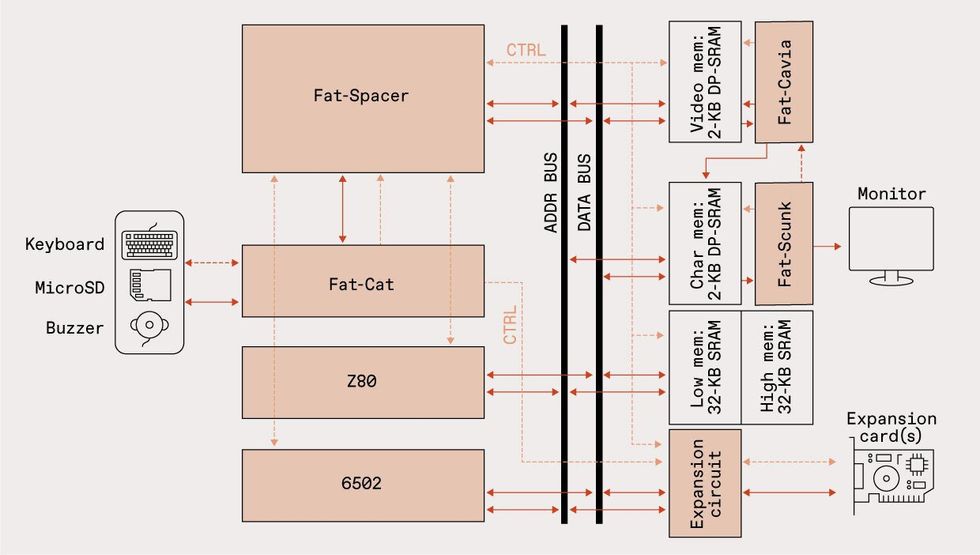

The Z80 and 6502 processors use different control signals to interface with memory and interface chips. A reprogrammable logic chip, dubbed Fat-Spacer translates these signals as required. Another reprogrammable logic chip handles storage and the keyboard interface, while a third generates video signals. James Provost

The Z80 and 6502 processors use different control signals to interface with memory and interface chips. A reprogrammable logic chip, dubbed Fat-Spacer translates these signals as required. Another reprogrammable logic chip handles storage and the keyboard interface, while a third generates video signals. James Provost

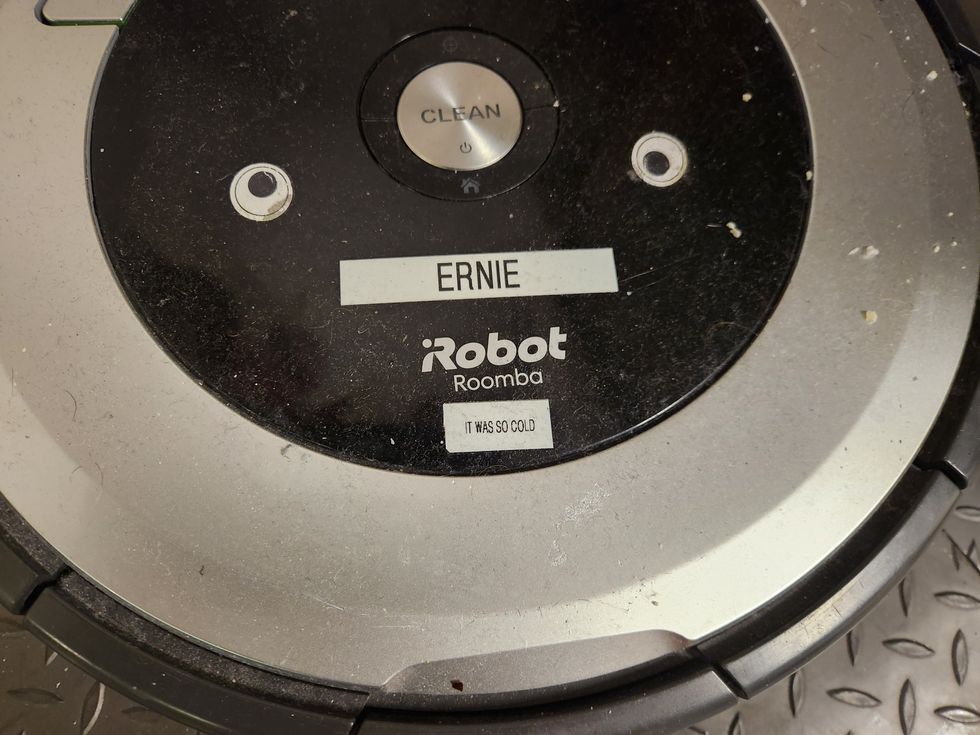

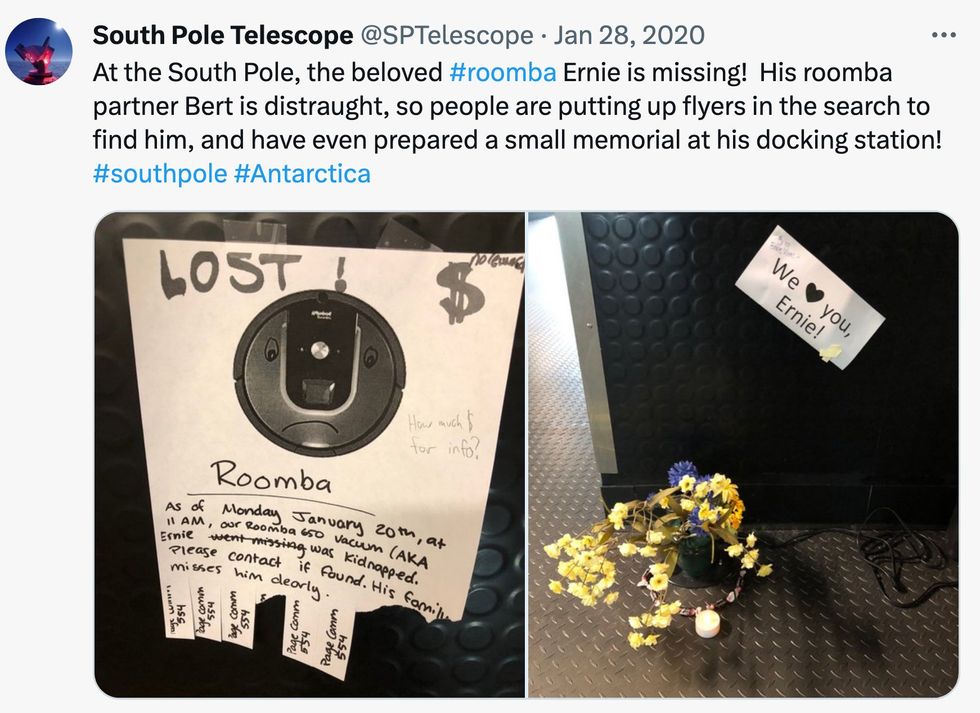

Ernie, a Roomba living at the south pole.

Ernie, a Roomba living at the south pole.

Sam, the “station cat.”Kyle Ferguson

Sam, the “station cat.”Kyle Ferguson A recent picture of Ernie, who is currently living underneath a popcorn machine.Kyle Ferguson

A recent picture of Ernie, who is currently living underneath a popcorn machine.Kyle Ferguson

A 70-year-old Latimer [in the foreground seated at the right side of the table] was photographed along with other Edison Pioneers in 1918.Lewis Latimer House/Alamy

A 70-year-old Latimer [in the foreground seated at the right side of the table] was photographed along with other Edison Pioneers in 1918.Lewis Latimer House/Alamy This highly detailed mechanical drawing of an Edison lamp appeared in Latimer’s 1890 book “Incandescent Electric Lighting.”

This highly detailed mechanical drawing of an Edison lamp appeared in Latimer’s 1890 book “Incandescent Electric Lighting.” The Latimer House Museum’s collection includes a lightbulb featuring one of its namesake’s inventions—a filament that improved the performance and lifespan of incandescent bulbs.Alamy

The Latimer House Museum’s collection includes a lightbulb featuring one of its namesake’s inventions—a filament that improved the performance and lifespan of incandescent bulbs.Alamy